A lawyer’s courage during state’s darkest days

November 5-11, 2018

By Jay Edwards

Almost a century ago, in fall of 1919, one of the greatest tragedies in the history of America took place in eastern Arkansas near the small community of Elaine. In those days, in the south, cotton was the number one commodity and white land owners found and exploited cheap labor from African Americans. The delta acres of the south, particularly Arkansas and Mississippi, were the main cotton producers in the world, and landowners agreed to split the bounty with black laborers. But more times than not that didn’t happen.

“They kept the workers in debt, both blacks and whites, but mainly the blacks,” said Oscar Fendler, a Delta attorney. “They never could get out of that debt.”

Then in 1917, the United States entered World War I and black Americans fought bravely and honorably alongside white Americans. When they returned home after the war, they heard the words of the black historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois, which burned into their psyche, “By the God of heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”

This new determined mindset from black Americans was met with violence by many whites and came to a head in the 1919 “Red Summer,” so named for all the bloodshed. Race riots took place in over 300 cities across the country, and not just the south.

On Sept.30 of that year, in Phillips County, Arkansas, a group of black men and women were holding a late night secret meeting in a small rural church. They were organizing a union, to stand up to the men whose land they worked and to demand what was rightfully theirs to begin with. But word leaked out about the meeting and three white armed law men made their way to the church, intent on breaking up the sharecroppers’ plans.

What the lawmen hadn’t learned was that organizers of the secret meeting had placed armed guards around the church. A shootout occurred and W. A. Adkins, a security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad was killed and Charles Pratt, Phillips County’s deputy sheriff, was injured.

There was a quick and brutal retaliation from the white community. The sheriff called for white citizens, from both Arkansas and Mississippi, to arm themselves and respond with force, basically declaring open season on black people.

The result was horrific, with estimates of murdered blacks running well into the hundreds.

Historian Tom Dillard says that “a charge was leveled against the black population that they were in a secret conspiracy to rise up and to overthrow the white power structure and the land-owning class in eastern Arkansas.”

Telegrams were sent from the Phillips County authorities to Governor Charles Hillman Brough, who sent in 500 soldiers from Camp Pike in Pulaski County. This action was no relief for the black population, however, as reports came in of more killings of blacks by the white soldiers. Sharpe Dunaway, an employee of the Arkansas Gazette, alleged that soldiers in Elaine had “committed one murder after another with all the calm deliberation in the world, either too heartless to realize the enormity of their crimes, or too drunk on moonshine to give a continental darn.”

Sixty-seven black men were sent to prison and 12 were tried before an all-white jury. A huge mob gathered outside the courthouse and it was made very plain that if the verdict for the 12 men was not death, there would be a lynching.

Inside the courtroom things were just as bleak for the 12 defendants. The trial began before their attorneys even had a chance to talk with them. The jury spent almost no time before finding each man guilty and the sentence for all was death. And the state of Arkansas was satisfied.

Scipio Africanus Jones

But a prominent black attorney from Little Rock was far from satisfied.

Named after a Roman general, Scipio Africanus Jones was born near the small community of Tulip, Arkansas, in Dallas County. Jones’ mother, Jemmina Jones, was a 15-year-old slave when her mixed-race son Scipio was born. She was owned by Dr. Adolphus and Carolyn Jones, who primarily wanted her as a companion for their daughter Thresa when the girls were young. Thresa, a year younger, became Jemmina’s best friend.

Dr. and Mrs. Jones died when Thresa was 9, and she and Jemmina were moved to the house of her uncle, Dr. Sanford Reamey, who later fathered Scipio.

Driven to succeed, Scipio Jones worked his way through college and went on to study law. When he passed the Arkansas bar examination in 1889, Jones became one of Little Rock’s first “home grown” black lawyers.

Three decades later he became determined to save the Elaine 12 from execution. What Jones didn’t know was that the assistant secretary and chief investigator of lynchings for the NAACP, Walter White, was already on the case. White recruited Colonel George Murphy, an Arkansas lawyer and the state’s former attorney general to represent the condemned men.

Jones and Murphy teamed up and headed east from Little Rock to Helena. But racial tensions were still very high in the area and Jones had to know the possibilities of danger for him that waited ahead.

“What I find so extraordinary about Scipio Africanus Jones is his courage,” said author Grif Stockley. “His willingness to go to Helena, knowing that his life was always at risk as soon as he crossed the county line.”

Jones, aware of the threats to his life, slept in a different home every night. By day he and Murphy worked on their motion for a new trial. They said that the presence of the mob and their client’s testimony about use of torture made a fair trial for the men impossible.

But the judge denied their motion.

Jones and Murphy immediately appealed to the state Supreme Court, which ordered a new trial for six of the 12 men, on technical grounds, but allowed the original sentences of death to stand for the other six.

Murphy died in October of 1920, and with six of the defendants only days from being executed, Jones’ hope was wearing thin. The six condemned men watched from their cells as prison carpenters built their coffins. Jones knew the Supreme Court would not stop the executions but he surprised everyone, with only hours left, by getting a delay from the chancery court.

“Some folks perhaps would have even questioned the wisdom of Mr. Jones filing a petition in the chancery court, which had no jurisdiction,” said Judge Wiley Branson Jr. “Ultimately and practically speaking it turned out to be a brilliant move … because he did secure a delay … which bought him time to pursue more appropriate appeals.” Weeks later the Arkansas Supreme Court removed the stays, but Jones had gotten the necessary extra time to prepare a motion to be filed in the federal district court. The case was Moore vs. Dempsey, and the strategy by Jones had saved their lives.

The Moore defendants were granted a new hearing after the U.S. Supreme Court, under the guidance of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, ruled that the original proceedings in Helena had been a “mask,” and that the state of Arkansas had not provided “a corrective process” that would have allowed the defendants to vindicate their constitutional right to due process of law on appeal.

Instead of pursuing a new hearing in federal court, in March 1923, Scipio Jones entered into negotiations to have the Moore defendants released. To be released, the men would have to plead guilty to second-degree murder and agree to a sentence of five years from the date they were first incarcerated in the Arkansas State Penitentiary. Finally, on January 14, 1925, Governor Thomas McRae ordered the release of the Moore defendants by granting them indefinite furloughs after they had pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. In the interim, Jones had secured the release of the other Elaine defendants.

One of the finest tributes to the brave lawyer came nearly 80 years ago in the black newspaper, The Arkansas Survey:

“Mr. Jones went to Helena and took charge of the case when Helena was a seething caldron of hate and the least indiscretion meant death. For four years he traveled and investigated and pled, until the 13th of January, when Governor McRae opened the prison gates to the last of the rioters. All hail Jones. Praise him for his knowledge of the law, for his nerve and his sagacity. He will receive little glory. But it is the great state of Arkansas, which is the real beneficiary of his service, and the people of America as well.”

Sources: The Elaine Riot: Tragedy and Triumph, Written and Directed by Richard Wormser (2011); The Arkansas Encyclopedia Of History and Culture – The Elaine Massacre; Scipio Africanus Jones (Chickenbones: A Journal)

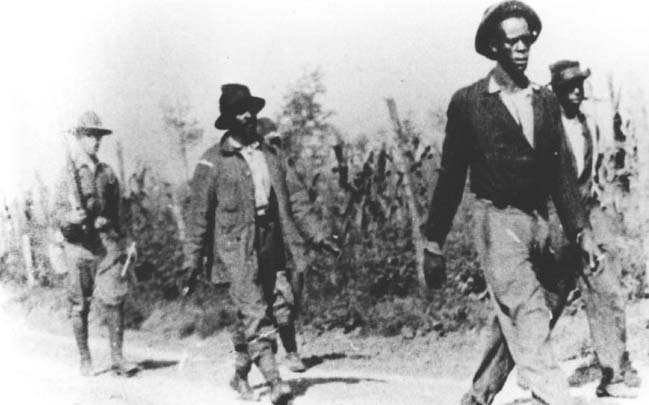

(Photos Courtesy of the Arkansas State Archives)

PHOTO CAPTIONS:

1. Charles H. Brough (right) talks with a U.S. Army officer in the aftermath of the Elaine Massacre; 1919.

2. African American men taken prisoner during the Elaine Massacre by U.S. Army troops sent from Camp Pike; 1919.

3. Charles Hillman Brough addressing a crowd in Elaine after the Elaine Massacre; October 1919.