Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Saline County, Arkansas

November 12-18, 2018

By Cody Berry

Indian Removal was not a new idea when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act up to President Andrew Jackson in 1830. Either acting out of paranoia, or pure prejudice, Jackson wasted no time when he signed that controversial act into law. The Cherokees were the first to push back and the Supreme Court agreed with them. Their forced removal was indeed unconstitutional, but that didn’t stop it from happening. Jackson supposedly said that Chief Justice Marshall had his ruling now “let him enforce it.”

All tribes in the southeastern United States were forced to sell or trade their lands for new lands in the newly created Indian Territory on Arkansas’s western border. Before that, the Quapaw, Osage, Caddo, and some Cherokees were forced out of the state by the Territorial government. But after 1830, all tribes in the southeastern states were assigned an agent from the Office of Indian Affairs to oversee their removal and subsistence. Agents also managed the tribe’s funds, sometimes not so wisely. Textbooks call this the “Trail of Tears,” and Arkansas has more trails than any other state. In addition to leaving their homes behind, and finding food, the tribes were forced to brave harsh weather and devastating diseases like cholera and smallpox.

The Choctaws and Chickasaws crossed through Saline County on a few occasions accompanied by their families, slaves, livestock, and agents. At the time, there was a ferry operated by William S. Lockhart at Saline Crossing and a depot near Hurricane Creek which were used by both tribes. Lockhart was the first white man to settle in Saline County and by 1831 his home on the banks of the Saline River in present-day Benton functioned as a post office, hotel, and tavern. The village which sprang-up around Lockhart’s tavern attracted many travelers on the Old Southwest Trail.

In Winter 1832, the Arkansas Gazette reported that Lt. Stephen R. V. Ryan’s group had crossed the Saline River near present-day Benton. Ryan’s party consisted of 594 followers of David Folsom (Choctaw), who left Little Rock on Dec. 28 and arrived at the Saline River two days later. Followers of Choctaw Chief Netachache passed through under the direction of Wharton Rector. There were 1,300 Choctaws in Rector’s party who had left Little Rock on Jan. 28 with 50 large wagons, and by Feb. 1, they were followed by another 200 under Samuel M. Rutherford. On Jan. 4, 1832, the Gazette reported a “party of Choctaws,” from Camp Pope in Little Rock, “left the Saline, 30 miles south of this, on Saturday morning, and were proceeding very finely when last heard from.” This was probably Rutherford’s party.

Other parties led by David Folsom and Greenwood Leflore passed through with their agents Joseph A. Phillips and S.T. Cross respectively. Cross led 600 while Phillips led another 800, who were battling cholera at the time. Phillips’s group camped at the Hurricane Creek depot before crossing the Saline the next day and heading on to Trace Creek. Phillips recorded losing several Choctaws to cholera in Saline County. Phillips’s group were followed by another 47 Choctaws, their slaves, and a herd of 244 horses belonging to the Leflore Party who crossed the Saline on Nov. 24. The last group of Choctaws to cross the Saline arrived at Little Rock on Nov. 20, 1833 and crossed the Saline later that day.

The Chickasaws began leaving their homelands in 1837. But, unlike other tribes, the Chickasaws paid for their own removal and subsistence. That year, Agent John Millard led a group of 516 Chickasaws to Memphis. From there, they went to Little Rock, then a revolt took place that caused them to head for the Red River, taking 500 horses with them on the road southwest of Little Rock. Once Millard re-gained control of the group, the main body, led by a Chickasaw named Sealy, crossed the Saline on Aug.13. Sealy’s Rebellion caused the War Department to stop supplying rations on the Southwest Trail.

However, a smallpox epidemic hit Fort Coffee in Indian Territory soon afterwards. This forced removal agents to follow the Southwest Trail despite their previous objections. Another factor was the insistence of the Chickasaws to go where they wanted at the pace they wanted. They were paying their own way. Sometimes the Chickasaws would stop to hunt bears and other wild game in Arkansas, much to the annoyance of their agents.

The Choctaws typically went from Saline Crossing to Rockport, then to Caddo Valley, then Antwine, South to Washington, and from there west to the Choctaw Nation. By the time the Chickasaws had come, a new road had been cut in 1835, they would follow the Southwest Trail to Antwine, then to Murfreesboro and from there to Ultima Tule on the Choctaw Line just west of present-day DeQueen.

For nearly a decade the Choctaws and Chickasaws crossed the Saline River while following the Old Southwest Trail. Lockhart’s settlement, Saline Crossing, was all but non-existent by 1836, when Arkansas achieved its statehood and the town of Benton was founded just north of Saline Crossing. Both settlements were built on the Southwest Trail making them important stops for travelers and emigrating tribes between 1831 and 1840, when removal ended.

PHOTO CAPTIONS:

1. Depiction of modern day Saline Crossing, with the Union Pacific Bridge nearby. (Photos courtesy of Loran Lyle)

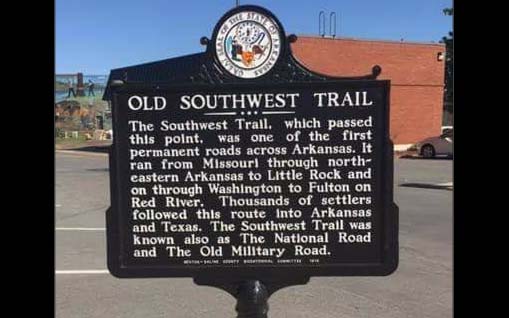

2. Today a historical marker denotes the Old Southwest Trail, one of the first permanent roads in Arkansas. As told above, the trail’s history is intertwined with Indian Removal. (Photo courtesy of Larry Bueche of Saline County Preservation, Inc.)