The legend behind the man: Pike walked to Arkansas, left big footprint

July 2-8, 2018

By Jay Edwards

Driving through parts of Little Rock and Hot Springs, one cannot help but notice Albert Pike’s name. The lawyer, Civil War general, and leader of the Freemasons migrated to his new home in the Natural State, from Massachusetts in the mid-1800s. How did this man with entrenched ancestral roots in the country’s original colonies find his way to Arkansas? It was not a straight path and likely began as so many adventures did in those days, through the restlessness of youth and an itching curiosity to see what lay West.

Pike was born in Boston in 1809, to a father who was a cobbler by trade and to a mother who was a “very beautiful woman,” as her son described her.

When he reached the age of 16, he took and passed the entrance exam to Harvard, and was accepted, but could not afford the tuition. Had he enrolled, he would have been in the same class as Oliver Wendell Holmes. Instead of learning in the classrooms he began teaching in them, in rural towns like Gloucester and Fairhaven. During this time he wrote poetry, and became so accomplished at the craft that many experts felt he might have become one of America’s greats, had that been his desire.

In one of his early poems, titled “Fantasma,” Pike wrote of a hopeless love he felt for a girl who was much wealthier than him. Some believed this may have had a bearing on his departure for the West, as he wrote, “Weary of fruitless toil he leaves his home, To seek in other climes a fairer fate.”

Perhaps it was unrequited love that drove young Pike, or maybe it was a bit of the same DNA possessed by ancestor Zebulon Pike, the explorer who gave his name to Pike’s Peak in Colorado, and for whom Pike County, Arkansas is named. Whatever the reason, Pike left his home in March of 1831, on foot. By August he had nearly made it to St. Louis, where he threw in with a wagon train of settlers headed for Santa Fe, which was still part of Mexico.

He spent eight months in Santa Fe before deciding to travel again with a group of trappers, who were headed down the Pecos river into the Staked Plains. It was a difficult and dangerous journey and Pike nearly died, writing of the experience in his poem, “Death in the Desert.” But he survived and made his way east, traveling some 600 miles on foot before finally coming to Fort Smith, where he knew no one and had come to the end of his money. Never one to give up, in a short time the explorer poet was teaching school in a tiny log cabin near Van Buren, and at last tired of wandering, began to settle in to a new life.

It wasn’t long before Pike’s writing gained attention, from letters he’d sent to newspapers that supported Robert Crittenden in his run for Congressional territorial delegate. Pike signed the letters, Casca, after one of the Roman senators who killed Julius Caesar.

The well-written political articles, under the mysterious pen name, garnered so much notice that Horace Greely reprinted them in the New York Tribune. All of Arkansas was talking about the articles and wondering who this “Casca” really was.

It was Crittenden who finally took it on himself to find out, and he soon discovered the young man teaching in a log schoolhouse on the Little Piney River.

Pike’s revealing attracted the attention of Charles Bertrand, owner of the Whig Party’s newspaper, the Arkansas Advocate. Bertrand quickly offered Pike an editors position in Little Rock, which he accepted.

Pike married Mary Ann Hamilton on Oct. 10, 1834 and the couple had six children. Hamilton came from a wealthy family, which allowed her new husband to purchase an interest in the Advocate and the year after to buy it outright.

Still looking for challenges, and perhaps piqued by a part time job he gained as a clerk for the legislature, Pike enrolled in law school. After passing the bar he sold his interest in the Advocate and became a full-time lawyer.

His practice soon flourished, with clients that included tribes from the Indian Territory. From 1836 to 1844, Pike was the first reporter of the Arkansas Supreme Court, tasked with keeping notes on the relevant points in court decisions, then publishing and indexing the court’s opinions.

In 1845 he supported the cause of the annexation of Texas from Mexico, which led to the Mexican War the following year. Pike served as captain of the Little Rock Guards, an Arkansas cavalry regiment under the command of Colonel Archibald Yell. But he soon decided that the senior officers of his regiment were incompetent, and he shared those observations with the people back in Arkansas through letters to the newspapers. One of the officers Pike targeted in his letters was Colonel John Selden Roane, who insisted Pike apologize or “give him satisfaction.” Pike didn’t recant and the two soldiers dueled near Fort Smith, on a sand bank in the Arkansas River. Each man fired his weapon, and both missed, ending the duel and restoring any honor that may have been lost.

After the Mexican War Pike again took up the cause of the Native Americans, for whom he felt great sympathy over their treatment, leading him to join Abraham Lincoln in the Choctaws case in front of the Supreme Court.

Because of those efforts in the Native Americanw Territory, the Confederate War Department appointed him a brigadier general in the Confederate army in August 1861 and assigned him to the Department of the Indian Territory.

In the spring of 1862, Pike, along with an Indian force of 900 men, joined the Confederate soldiers at Pea Ridge in the battle against the Union Army. Even though the South outnumbered the Union Army in this battle, which was unusual, the Rebels were defeated. Afterward, Pike and what was left of his regiment, returned to the Indian Territory.

On July 12, 1862, Pike resigned from the army and retired to Greasy Cove in Montgomery County. He was appointed as a judge of the state Supreme Court in 1864. But in 1865, restless again, he moved around to places like New York City, Memphis, Washington D.C., and even Canada, always finding a newspaper to edit and a political cause to join.

Of the vast interests in Pike’s life, one of the strongest were the Masons. He had joined the fraternal group in 1850 and helped create the Masonic St. Johns’ College in Little Rock that same year. He was elected grand commander of the Supreme Council and in later years spent much of his time rewriting the rituals of the Scottish Rite Masons.

Pike died at the Scottish Rite Temple in Washington D.C. on April 2, 1891.

Authorities named the first highway between Hot Springs and Colorado Springs, the Albert Pike Highway. And the Albert Pike Hotel and the The Albert Pike Memorial Temple in Little Rock both bear his name. His Masonic brothers erected a statute to him in 1901 in Washington D.C., which in recent years has been the subject of controversy because of his Confederate roots. Many are calling for the statue’s removal. Whatever his politics, it can never be said that this explorer, teacher, journalist, poet, lawyer, and General, did not live a full life. Perhaps his fraternity of Freemasons remember him best when they write, “the life of Pike is a part of the romance of his country.”

Sources: masionicdictionary.com, littlerock.com, The Encyclopedia Of Arkansas History and Culture

PHOTO CAPTIONS:

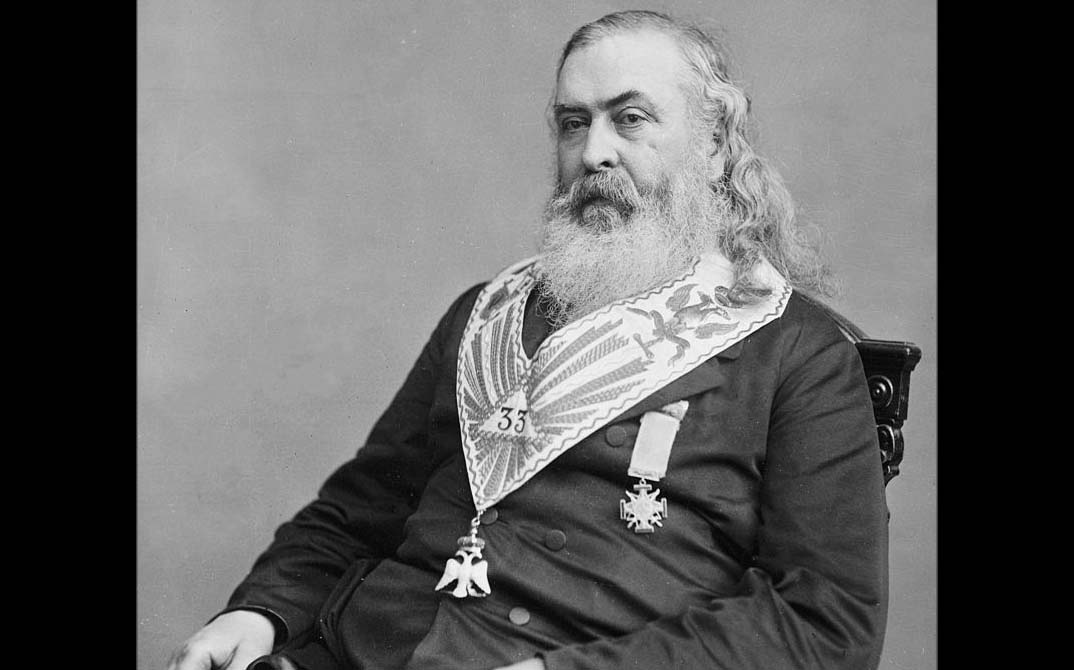

1. Albert Pike (Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.)

2. A look inside the Albert Pike Masonic Center today, located on Scott Street. (Photo courtesy of Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism)