Arkansas Natural Sky Association advocates for darker nights

April 24-30, 2023

By Jay Edwards

“This meadowlark perches on its native flower, singing its mating song. It’s customary for meadowlarks to sing toward the rising sun. This one however, was mistaken, by the lights of Rapid City at 2 A.M. Despite being 60 miles south of the Rapid City border and well within the boundaries of Wind Cave National Park, this songbird was singing out much too early to attract a mate. Have you ever tried to attract a mate by calling them at 2 A.M.?

So why was this songbird so confused? Because improper lighting and the over-illumination of residential neighborhoods, business signage and streetlights, brighten our night sky.”

- International Dark Sky Association President Diane Knutson, from her 2016 TED Talk, “Why we need darkness to survive.”

It was 1977, when two fraternity brothers and I drove through the desert, not far out of Kingman, Arizona, on our way to Las Vegas. We had not yet reached the Hoover Dam when I spotted the glow of the light dome, rising above our destination, still over an hour away. It was quite a sight to behold and I never imagined at that moment it could be a bad thing. Fortunately, however, others long before me, did.

In her 2018 article titled “There goes the night,” which appeared in Knowable magazine, Stephanie Pain remembered Ludwig Kumlien, a highly respected Wisconsin ornithologist, who on September 23, 1887, climbed up the tower on top of the Industrial Exposition Building in Milwaukee, where he discovered why the structure was proving lethal to migrating birds. He found that from sunset to near midnight, the tower was lit by four large floodlights, which attracted birds flying south and causing them to fly into wires, windows and each other. Kumlien’s scientific report on the dying birds is the first account of the “ecological downside of lighting up the night sky. Today, the United Nations reports that artificial light increasingly alters natural patterns of light and dark within ecosystems and contributes to the deaths of millions of birds each year. Light pollution can cause birds to change their migration patterns, foraging behaviors and vocal communication, resulting in disorientation and collisions.

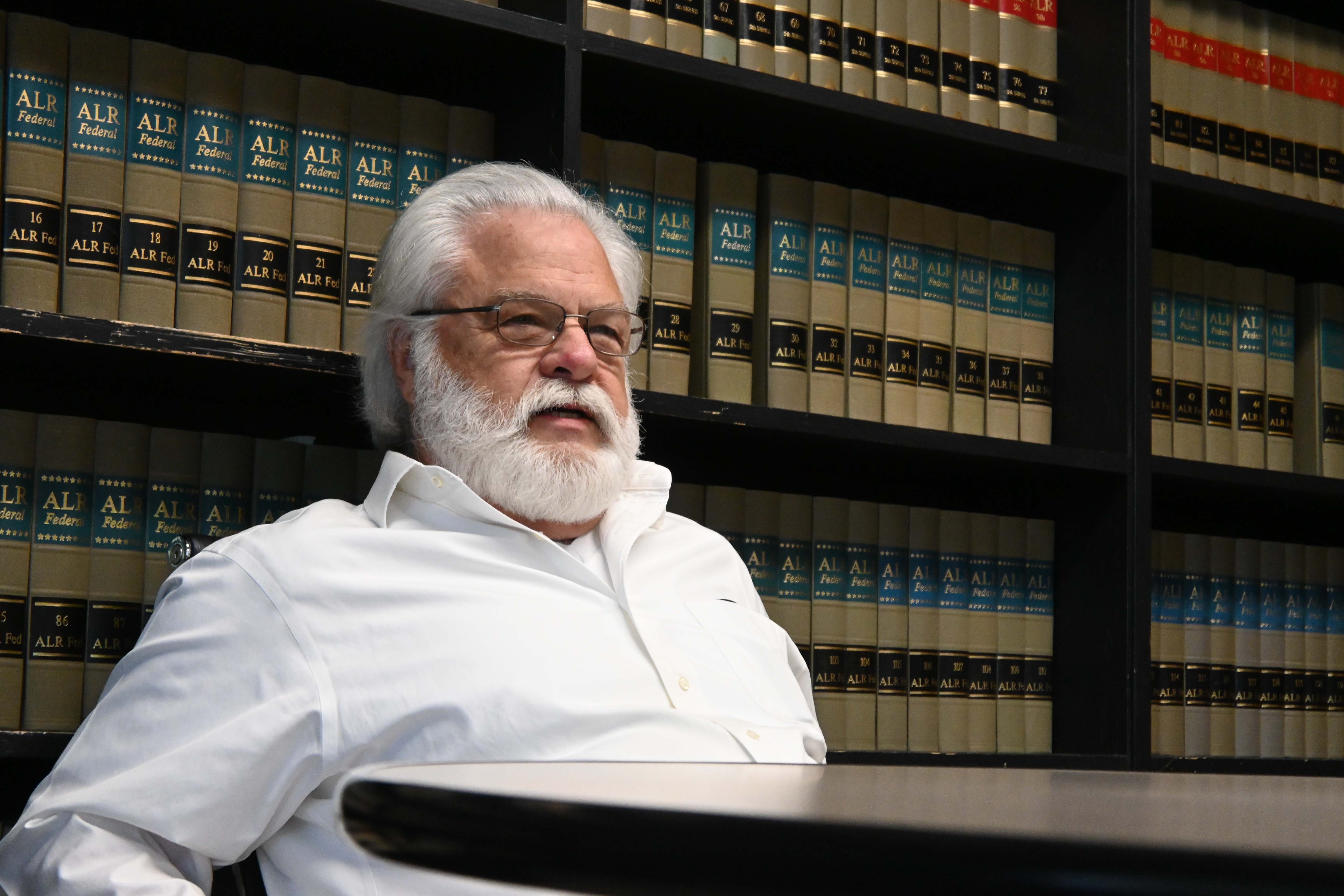

A few weeks ago, I was on my way to interview Bruce McMath, a retired Little Rock attorney who is the chapter chair of the Arkansas Natural Sky Association (ANSA). Bruce assumed leadership of the ANSA in 2015, and through his efforts and those of other passionate volunteers, the Arkansas affiliate of the International Dark Sky Association is responsible for certification of the Buffalo National River as an International Dark Sky Park in 2019. During his two-decades of service to ANSA, Bruce created the city survey of lighting plans, giving cities a clear blueprint for measuring progress toward achieving more responsible lighting. He has also led educational outreach for students and others in several areas of the state by providing access to telescopes and training in night sky observation and appreciation. The International Dark Sky Association honored Bruce last year with the Bob Gent Community Leadership Award, which is given to an IDA Chapter or Chapter member who has demonstrated outstanding achievement at the local level in combating light pollution and fostering support for IDA’s mission and programs.

As I drove to meet Bruce, my phone rang, and like all responsible citizens I pulled over and took the call. It was my friend Carol, and after greeting each other I told her where I was going and the purpose of my meeting. Her response was something to the effect of, “Well, I’m a woman who lives alone and I’m not turning my lights off. As far as I’m concerned, the brighter at night the better!”

Not having done that much research, it seemed to me that Carol made a pretty good point. If most of the lights were turned off at night wouldn’t that be an invitation for criminals to prowl about more freely? I’d have to ask Bruce about that one.

In a 2015 article for The Conversation, Professor Richard Stevens of the University of Connecticut wrote that in the days before electricity came along, people slept differently than they do now. It was dark for half of the 24 hours in a day and we slept for eight to nine hours in two separate periods, while being awake, but still in the dark, for three to four hours.

That wasn’t the case after electricity arrived in the 19th century. Today, more that 80 percent of the world lives with light pollution, which messes up our circadian rhythm, the natural, internal process that regulates the sleep–wake cycle of all living organisms and repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythm affects all physiological processes, one of which is the production of melatonin, the hormone that is released during the dark and reduced during light. When melatonin is decreased we sleep less and naturally become more fatigued, which leads to anxiety, stress, and other unpleasant health issues. More recent studies have found connections between less sleep, low melatonin levels, and cancer. People who work night shifts have been found to have lower levels of melatonin in the blood.

But these days one doesn’t have to work the graveyard shift to suffer ill-effects of unnatural light. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs), those low-cost and energy efficient bulbs found in homes and industrial and city lighting, emit blue light, the same light found in cell phones and computer devices. And it is the blue light of the spectrum that reduces levels of melatonin in humans.

I met with Bruce in his conference room at the McMath Law Firm and asked him how he got involved in ANSA. He smiled and began reminiscing.

“The Sputnik went off when I was about eight years old and I became fascinated with space travel and rockets, which led to an interest in astronomy. Years later I tried to get my oldest son interested in the stars so I bought a telescope. I got hooked and he didn’t. So, I have had a long-standing amateur astronomy hobby. Then when I retired I said, it’s time somebody did something about this light pollution.”

“We were able to get the Buffalo designated as an International Dark Sky Park, which took about two and a half years. We started out talking to Ouachita National Forest, but they didn’t have the staff and interest waned. The town of Gilbert, on the Buffalo, got on board and we were able to get them a new set of streetlights. We’ve worked with the local chamber in Searcy County and they are very supportive.”

I asked Bruce where the best places are in the state for the darkest skies.

“Probably the darkest places in the state are in the Ozark and Ouachita National Forests. But the thing about places in Arkansas, if it has dark skies, it also has trees. And many of those places are in our state parks and they close at night. To be a dark sky park there must have access so people can come at night. We were close to getting Mt. Magazine designated as a dark sky park. They were on board. But the pandemic came along and the park ranger who was driving the effort moved away. Now we are working on some promising things at Lake Ouachita.

I asked him if it is easier in the western states, where the larger cities and their lights are more spread out.

“Flagstaff, Arizona was the first US city to implement a responsible lighting ordinance,” he told me, “which passed in 1972. Today, you can see the Milky Way from inside the Flagstaff city limits.” In a talk he gives on the subject, Bruce compares Flagstaff to Conway, which is about the same population. “But Conway has six times the sky glow. A lot of that is wasted energy. My dad use to say, ‘Turn the light off if you’re not using it.’ In North Little Rock there is a health facility whose parking lot lights are occupancy activated. They are off until you drive into the parking lot.”

I told Bruce what my friend Carol said to me earlier about not giving up her outside night lights.

“Utility companies have sold people on the idea that lights deter crime,” he said. “But criminals are human, and they need light too. If you light someplace that isn’t being observed, you won’t deter crime, in fact, you might attract it. So, we have lights all over the country that are on all the time, to no purpose, creating carbon, wasting money and often contributing to crime. A 100-watt light bulb left on all night for a year, generates a half-ton of carbon dioxide.”

“The city of Hot Springs park system will not light their parks at night. Why? Because it attracts vandals and criminal conduct. There is a school district in Washington state that during the last energy crisis turned off their lights at night. What happened? Vandalism went down. Criminals are people and people are scared of the dark.” Bruce wanted to be clear that those who advocate for proper lighting aren’t out to take away outdoor lights from homeowners.

“We just want lights to be the proper kind and effective,” he says. “The Illumination Engineering Society is a professional organization of engineers who are students of lighting and how you use it for human benefit and they tell you the most effective security light in a residential setting is a light on a motion sensor, because you don’t attract or call attention to your property. But if someone does approach there is a sensation of having been detected. It’s far more effective than a light which is always on.”

I thanked Bruce for the interview and told him I looked forward to learning more and hoped to be seeing more stars in the future. He told me for a good look at the Milky Way I needed to come to the 2023 Natural Sky Festival, that takes place September 14 - 16, on the grounds of the Bear Creek Log Cabins, a few miles from the Tyler Bend Campground on the Buffalo. I told him I’d see him there, but…not in too much light.

For more information on the festival and other ANSA projects go to darkskyarkansas.org