Trudging the road of happy destiny

November 10-16, 2025

By Colin Jorgensen

I’m a cis white male middle-aged American. I’ve already enjoyed multiple lifetimes worth of privilege associated with my immutable characteristics and life circumstances.

I spent the first 30+ years of my life enjoying the blissful ignorance of overconfidence, and truly believing I’d never been wrong about anything, never lost an argument, always won at everything. I’m competitive by nature.

I’m a lawyer, and a good one.

For about 15 years—in theory, my best years—I was faithfully committed to booze. By my late twenties, daily drinking had become miserable, but I couldn’t stop. I eventually admitted my powerlessness over alcohol (alcoholism) and became willing to accept help, which was freely provided in the rooms of recovery.

I’m grateful for my addiction experience and the (tiny bit of) humility that was gifted to me along with countless other gifts and promises of sobriety. I know what it’s like to be trapped in hell, and I know what it’s like to be shown the way out.

I have a high-performance brain, especially without the bondage of active alcoholism, which hijacks the brain. I’m good at tests, legal writing, quickly producing quality work product, and a few other specific things. My best grade in law school came in a first-year class where most folks didn’t finish the test in the allotted time. I misread the clock at the outset, set the wrong pace for myself, and turned in my exam an hour early, thinking we were seconds away from the end. I was surely drunk already when time was called, while many classmates had to submit incomplete exams. I tend to perform well under pressure.

I would describe my baseline state of mental well-being as “happy.” I’ve felt happy for most of my individual moments and days, and most of my aggregate life. I believe there is something to the notion that happiness is something we seek for its own sake, perhaps even the highest good.

I’m happy about being happy. One of my friends in recovery likes to accuse me of being “pathologically happy”—which is hilarious and mostly true, and which is meant as a high compliment and aspiration. Throughout my life, I’ve often referred to myself as the luckiest person alive or the luckiest person you know. And I believe it.

I’ve never thought of myself as a nervous person, but I’ve always been very high energy and relentlessly positive—except for those final few years of miserable drinking.

In the summer a few years ago—more than a decade after my last drink (one day at a time)—my wife was invited to the White House for an event. She invited me to accompany her for her trip, though I was not invited to the White House. We booked a fancy room at the Hay-Adams hotel and we hopped on a plane to Washington, D.C.

I’ve always been uncomfortable with flying, but willing to tolerate it. I don’t like heights, and I have a long history of physical injuries that I attribute at least partially to gravity. This particular flight to D.C. was very turbulent. I don’t like turbulence. This was not turbulence where somebody gets injured or killed from extreme bouncing. It was two solid hours of persistent mid-level turbulence, and I think I held my breath for the entire two hours. But we landed safely in D.C., went to check into the hotel, and went to a nice restaurant for lunch. After lunch, my wife and I took a long walk along the mall, exploring a few museums. We were having a blast, and I was grateful to be there with my wife despite the awful flight.

Several hours after we landed in D.C., I began to grow hot (not unusual for me) and tired (very unusual for me). We had to stop for me to rest a few times (very unusual), but we eventually made it back to the Hay-Adams. My wife grew concerned about my apparent extreme fatigue, but I insisted that I was just tired for reasons I couldn’t explain. In the hotel lobby, my condition deteriorated, and I collapsed into a chair because I could hardly stand. My wife got me a soda because she thought maybe I was having a blood-sugar problem, though I don’t have blood-sugar problems and we ate lunch just a few hours earlier.

I gathered the strength and resolve to slowly get on the elevator and up to our room, where I collapsed on the bed. I’ve never felt so weak in my life. I could barely move. For a few hours, I rested—though I didn’t sleep, I laid perfectly still. Laying perfectly still is not something I generally excel at—but in this moment in time, it took all the strength I could muster to simply talk or raise my head.

I eventually sat up and started to feel somewhat better. My wife and I did not know or understand what was going on with me, but we were both hopeful that whatever it was, it was passing. We eventually decided to leave the hotel to get dinner at a nearby restaurant.

As soon as I was up and moving around (slowly), the extreme fatigue began setting in again. When we walked outside, I couldn’t take a few steps without stopping to rest, and the utter physical weakness kept getting worse and worse. I told my wife I couldn’t walk to the restaurant and needed to go back to the hotel room. We eventually made it back to the room, and my wife got us takeout for dinner in the room. I stayed in bed until the next morning. When I stopped trying to move around and laid still, I thought my condition improved.

Whatever was happening to me, when it overwhelmed me as it continued to do, I felt like I was struggling to breathe, and my heartbeat was out of sync, and I was essentially paralyzed with weakness. Any physical movement required my full concentration, and it felt like I had to flex my muscles to their maximum strength, just to perform a simple movement.

The next morning, my wife got ready to go to the White House and we agreed that I would stay in bed and rest. I didn’t try to do much, but I could tell that I was still weak.

I also felt hung over from the difficulties of the day before.

My body ached all over with sore muscles. It felt like the soreness was derived from all that maximum flexing just to do something simple like sit up. It was a level of soreness that I’ve only felt before when I completely overdo it on physical activity to the point of exhaustion. But I barely moved the day before aside from walking around for a couple of hours.

When my wife returned from her event, I was not well, and we decided to go to a nearby medical clinic. As soon as we got downstairs and started walking outside (very slowly), I was overcome with another wave of whatever-the-hell this was. I could barely move, but we slowly made our way to a medical clinic that was probably two blocks from the hotel.

By the time we got to the medical clinic, I collapsed to the ground in exhaustion, sitting on the sidewalk, leaning against the storefront, not moving. I complained about my breathing and heartbeat and inability to move. My wife tried to get the medical clinic staff to come outside to see me, but they feared that I was suffering a heart attack and they would not come outside to treat me. My wife called an ambulance, and I was taken to a D.C. hospital emergency room.

We were at the ER for about 24 hours, completely missing our second night at the Hay-Adams. My condition stayed mostly the same—extreme fatigue, difficulty moving, difficulty breathing, difficulty with everything, and a persistent feeling that all my body systems were shutting down. The medical experts ultimately concluded that there was no detectable medical emergency or physical explanation for my symptoms. We were released just in time to return to the hotel to get our stuff and catch our flight home. My wife had to do everything because it took all my concentration and energy to move myself from place to place (very slowly).

Over the next several days back home, my extreme weakness and other symptoms slowly improved, albeit with a lot of two-steps-forward-one-step-back. I was physically sore all over for a week. I still felt like my systems were in partial shutdown mode. After a few days, I was able to walk around and do lightweight activities without completely exhausting myself. But sometimes there were episodes that came in waves and flattened me. During the episodes, it again took all my strength to do any physical movement, and I again felt short of breath. Over time, my general energy level returned to normal (almost?), and the episodes became less frequent and less severe—but they did not stop entirely.

The D.C. hospital suggested that I follow up with my physician, which I did, and he referred me to both a cardiologist and a pulmonologist. I wound up wearing a heart monitor for a month and doing a stress test with the cardiologist, after which he declared that “you have a beautiful heart!” The pulmonologist also conducted tests and concluded that my lungs were in fine shape.

In the months of consultation with my general practitioner and the cardiologist and the pulmonologist, I mostly recovered from whatever happened in D.C., but I continued to have episodes of various strengths and lengths of time. If a wave was particularly strong, I might be essentially immobilized for an hour or two, or for the rest of the day, with all the usual symptoms, and sometimes with soreness for a day or days thereafter.

About 6 months after the trip to D.C., my doctor and I agreed that what happened in D.C. was a severe anxiety attack triggered by the turbulent flight. It seemed impossible that a “panic attack” could be so powerful and could have such crippling physical effects for so long, but apparently it is not impossible, and it was the only reasonable explanation. This also explained the subsequent episodes/waves, which are simply additional anxiety attacks. And apparently, it also explains the weird stuff—like using all my strength to barely move, then being sore for days from that huge workout.

A few years have now passed, and I continue to have anxiety attacks of various strengths and durations, though I’ve not had another one as big and powerful as that first one. It is helpful to know what’s going on (or at least think I know), so I don’t fuel an anxiety fire with additional anxiety about a possible heart attack or something else scary but inapplicable. I know that I’m ok and it will pass eventually, even though it never feels that way. My doctor has prescribed medication, which I think has reduced the frequency and severity of the episodes, but I can’t be sure. It’s also helpful to know that additional help is available if needed, including counseling and peer support.

Even though I had several episodes while wearing the heart monitor and I swear I felt many irregular heartbeats, the heart monitor recorded nothing irregular. It’s helpful to know that even though it feels like I can’t breathe and my heart isn’t beating right, in fact I am breathing fine, and my heartbeat is totally normal.

I’ve confirmed that even though it feels like my body is shutting down completely, my body is not shutting down. I’ve also learned that when I feel like I need to flex to the max just to move around, I’m not really flexing to the max—but my brain thinks I am, so I feel that sensation in the moment. And sometimes I even feel soreness for days thereafter.

In sum, I’ve learned that this is all in my head! The weakness, the inability to move, the shortness of breath, the irregular heartbeat, even the muscle soreness that sometimes lasts days, are all hallucinations. It is the strangest thing—so frustrating yet reassuring at the same time.

The most important thing I’ve learned is that anxiety attacks are a common mental health challenge—not entirely understood, but a real thing. I’m not alone. And I’m not crazy, even though it feels crazy to have such strong bodily symptoms residing only in my mind.

The fact that I’m not terminally unique—that this is garden variety stuff that happens to lots of folks—was also one of the most important things I needed to learn about alcoholism. And the same is true for anxiety attacks and other mental health challenges. Nobody chooses or deserves to be an alcoholic, or to suffer panic attacks, and those who face such challenges should not be stigmatized. I have little control over the fact that I have anxiety attacks, and I sure didn’t choose it! But as with alcoholism, once a cucumber turns into a pickle, it can’t be a cucumber again. What was true before that mega attack in D.C. remains true after: acceptance is the answer to my problems today.

I’ve learned how to respond to the challenges of anxiety, and how to live well despite the challenges. I’ve learned to practice acceptance and stop asking why. I’m not ashamed to be a recovering alcoholic, and I’m not ashamed to experience severe anxiety.

Perhaps it is even true that, as with alcoholism, crippling anxiety has forced a reckoning that has ultimately made me into a better person.

Perhaps it is even true, as with alcoholism, that these symptoms and consequences of severe anxiety are the downside of many blessings that I enjoy—from my high-performance brain to my general happiness and love of life.

Perhaps it’s not possible to enjoy such magnificent blessings without overheating my brain on occasion. Who knows.

Regardless, I’ve come to believe that my blessings and curses are concomitant and inseparable. And again, I’ve stopped asking why.

It doesn’t matter if I’ve got it all figured out or not (I don’t!). I’m grateful for all of it. And I wouldn’t change a thing.

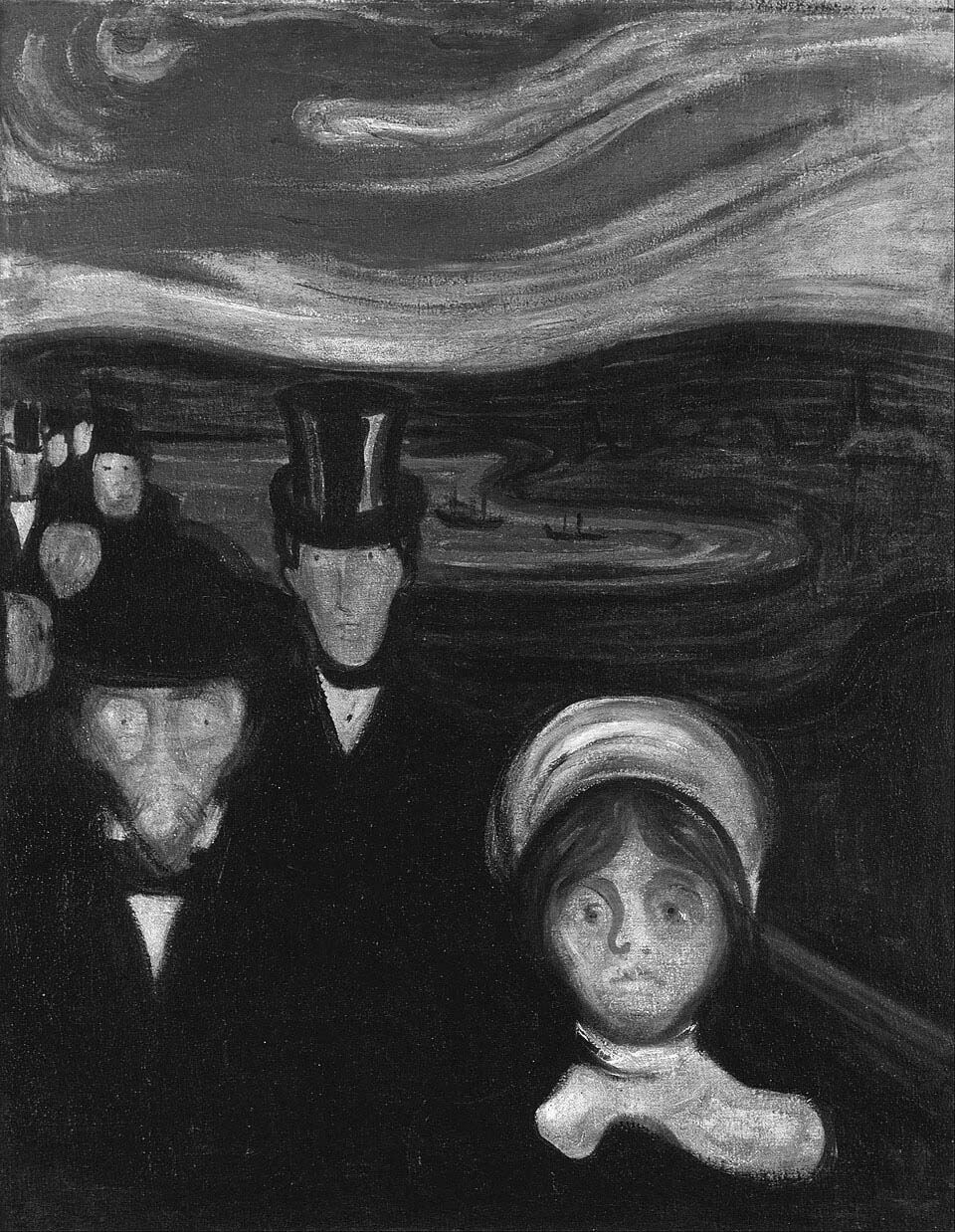

Photo Caption:

Anxiety by Edvard Munch.

Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons