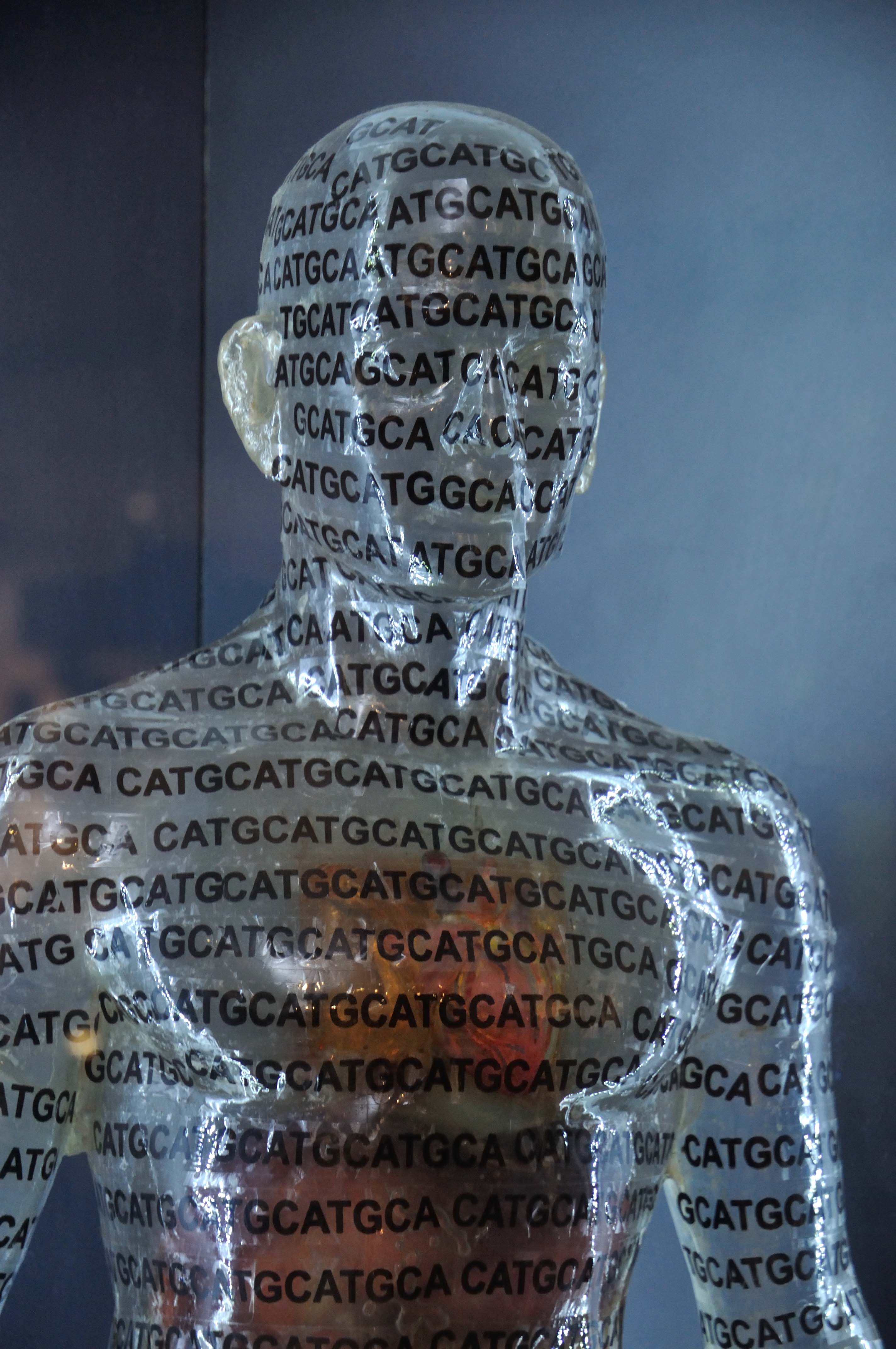

Who owns your DNA?

February 13-19, 2023

By Jay Edwards

The Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, on February 1, announced that women who do not have a higher genetic tendency for getting ovarian cancer should consider having their fallopian tubes removed anyway, if they are done having children and are having other abdominal surgery as well. There is no diagnostic test for ovarian cancer now and researchers doubt there ever will be. But there is a genetic test to see if a woman is at higher risk for the disease. Once armed with this knowledge, the women who test positive, often, like the actress Angelina Jolie, opt to have their fallopian tubes and breasts removed. But there was a time in the not-too-distant past that that test might not have been available to all. The reason was not medical, but monetary. There was a time when we did not own our genes. They were patented by biotech corporations instead.

Women who display a mutation in their BRCA gene have a 72% chance of getting breast cancer, a six-fold increase over women who do not have the genetic flaw. To make matters worse, a BRCA mutation also increases a woman’s chance of contracting ovarian cancer. While only 5-10% of breast cancer cases are caused by genes it is imperative that patients and their doctors have access to this vital information.

In 1994 Myriad Genetics patented the BRCA1 gene and a year later, BRCA2. The company then threatened a lawsuit against anyone who wanted to perform BRCA testing. At $3,000, the test was not cheap, and at that time, most insurance companies wouldn’t cover this cost. Even if a patient could afford the test, what if she wanted a second opinion? Because of the patent, Myriad was the only option.

Many in the field of medicine opposed these practices, from researchers and physicians to genetic counsellors, but until the ACLU stepped in, their voices weren’t really heard.

Jorge L. Contreras, the author of “The Genome Defense, Inside the Epic Battle to Determine Who Owns Your DNA,” was one of the featured authors at last October’s Six Bridges Book Festival, presented by the Central Arkansas Library System. To put it in a sentence, Cotreras’ book is about the patenting of human genes and the resulting legal case that wound up in the nation’s highest court.

Contreras begins his story in 2005, in lower Manhattan, when the young science adviser at the ACLU, Tania Simoncelli, poked her head into the office of Chris Hansen, one of the organization’s senior attorneys.

Simoncelli was smart, energetic, and passionate. She had turned down offers from five prestigious PhD programs two years earlier for the ACLU job. She and Hanson had become friends and he told her to come in.

She said she was looking for litigation angles for some of the science issues she had been thinking about. Hanson told her to fill him in on the more important ones. She began with brain imaging, which led them to admittance as courtroom evidence and similarities to lie detectors, which had been banned from courtrooms in most states. Hansen listened patiently, but Simoncelli must have sensed he wasn’t that impressed.

Her next idea concerned genetic discrimination. She asked Hansen if they could bring a lawsuit against an insurance company if they discriminated against someone who had the “wrong” DNA profile. People with HIV were being denied coverage. What was next? Someone with a genetic likelihood for heart disease or cancer?

Hansen liked the issue but told her without laws already in place it would be difficult. He asked her what else she had.

“There’s gene patenting,” she told him, and to explain gave specifics from a recent symposium she had convened for the ACLU in Boston.

“That can’t be right,” was Hansen’s response.

“Chris, it’s right, the Patent Office has been issuing patents on human genes for more than 20 years.”

Hansen wasn’t buying it. “They must be patenting the method for getting the DNA, or the function of the gene, or something like that,” he told her.

She told him that while that was true, it wasn’t what she was talking about. “The genes themselves are patented,” she said.

“I don’t believe it,” Hansen said. “Show me.”

That ended the meeting, or rather briefly recessed it.

Simoncelli went back to her computer and emailed Hansen three short articles on what was happening with gene patents. Twenty minutes later he rushed into her office.

“My God, you’re right,” he said, asking himself how the genetic code inside a person’s body could be owned by a company.

“Who can we sue?” he asked her.

The eventual answer to that question would be Myriad Genetics, headquartered in Salt Lake City. Hansen and his team chose Myriad to go after because of breast cancer, which affected so many families.

Eight years after Simonelli put the idea in Hansen’s head, after five back and forth rulings from lower courts, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that the central question for the justices in the case, Association for Molecular Pathology versus Myriad Genetics, was whether isolated genes are “products of nature” that may not be patented or “human-made inventions” eligible for patent protection.

Myriad’s discovery of the precise location and sequence of the genes at issue, BRCA1 and BRCA2, did not qualify.

“A naturally occurring DNA segment is a product of nature and not patent eligible merely because it has been isolated,” Thomas said. “It is undisputed that Myriad did not create or alter any of the genetic information encoded in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.”

In a 2021 review on Contreras’ book, reporter Amy Dockser Marcus of the Wall Street Journal wrote, “The case went through many legal twists and turns before reaching the Supreme Court in 2013, and its scientific arguments were no less tortuous. The book’s index includes a list of the metaphorical terms that were employed to argue for or against gene patenting. Justice Sonia Sotomayor allowed that someone might be able to get a patent on a new type of chocolate-chip cookie but not on the salt, flour, eggs, and butter used to make it. Why were genes different from cookie ingredients? When the Myriad lawyer tried to answer, he ended up using another analogy. A baseball bat, he said, doesn’t exist until it is isolated from a tree; the length of a bat is a “product of human invention” and thus would justify a patent.”

In his 9-0 court opinion Thomas wrote, “Myriad did not create anything. To be sure, it found an important and useful gene, but separating that gene from its surrounding genetic material is not an act of invention.”

In something of a concession to Myriad, the justices wrote that while the naturally occurring isolated biological material itself cannot be patented, a synthetic version of the gene material can be.

Photo Caption:

2. Edward R. Murrow: Who owns the patent on [the polio] vaccine? Jonas Salk: Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the Sun? See It Now (CBS, April 12, 1955)