1927’s Great Flood displaced 700,000 from homes

April 1-7, 2019

By Jay Edwards

“When it thunders and lightnin’

And the wind begins to blow

There’s thousands of people ain’t Got no place to go.”

~ Bessie Smith, ‘Back Water Blues,’ 1927

The massive devastation known as the Great Flood of 1927, and its far reaching and permanent consequences, actually began in the summer of 1926, when floodwaters from Illinois joined the relentless rains in the central Mississippi basin. By Christmas of that year the Cumberland River at Nashville, Tennessee crested to just over 56 feet, a record that still stands. Five months later the Mississippi River reached its mightiest, growing to a massive width of 60 miles in the delta lands below Memphis.

Ten states were affected by the disaster, with three, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, sharing the brunt. Of the 700,000 people left without homes, over ninety percent lived in these three states, and the economic consequences to Arkansas were the worst of the three. The Great Flood covered some 6,600 square miles in the Natural State, and nearly half of its 75 counties had water as high as 30 feet in some spots.

Total monetary damages to the ten states reached approximately $1 billion, which was one-third of the federal budget in 1927. Today that figure would amount to around $1 trillion. Over 500 people were killed, most of those in Mississippi and Arkansas.

Nothing quite like it has been experienced before or since. While researching in 2001 for their book on the Mississippi River, authors Steven Ambrose and Douglas Brinkley wrote of the flood, “And the rains came. They came in amounts never seen by any white man, before or since. They fell throughout the entire Mississippi River Valley, from the Appalachians to the Rockies. They caused widespread flooding that made 1927 the worst year ever in the Valley. More water, more damage, more fear, more panic, more misery, more death by drowning that any American had seen before or would again.”

It’s perhaps poignant that Ambrose and Brinkley chose the phrase, “seen by any white man,” seeing how the ones affected most severely by the Great Flood were African-Americans, those tens of thousands of plantation workers who were forced into the nearly impossible task, in miserable conditions, of strengthening the levees from Greenville, Mississippi to New Orleans. As the water continued its relentless rise, and white people were rescued to safer surroundings, the workers were left behind, stranded for days without adequate supply of drinking water and food.

The consequences of these decisions and actions of those in power, who controlled the nation’s resources, would cause permanent social and political changes in the United States. Up to this point, African-Americans had been mostly supportive of the Republicans and President Calvin Coolidge, primarily because of the stance the party of Lincoln took against slavery. After the Great Flood there was a large African-American shift to the Democrats.

The 1927 flood also added large numbers of African -Americans who would leave the south for better opportunities in northern cities, as part of the Great Migration, which had begun in 1916 and lasted until 1970, a period that saw more than six million people move their homes from the racially oppressive south, for new hope in the north and west.

Mother Nature was not the only one responsible for the Great Flood. The economy was booming in the 1920s and technology was keeping pace. Part of the advances were a system of levees put in place to hold back rivers. New areas of low land had been cleared for timber, and farmers and landowners were comfortable living below the massive river banks with these new levees to protect them.

In April of 1927, the heavy rains reached Arkansas and more than seven inches fell in Little Rock in just a few hours. The natural reservoirs of lakes and streams were already full and the bursting Mississippi River began rapidly sharing itself with the Arkansas River, as well as the White and the St. Francis.

The great pressure was too much for the levees and they began to give way. The September 1927 National Geographic reported the streets of Arkansas City were dry and dusty at noon, but by 2 p.m., “mules were drowning on Main Street faster than people could unhitch them from wagons.”

The deep swampy floodwaters stayed around for months, spotted with floating furniture, store goods and dead animals. Farmers were unable to plant crops and outbreaks of malaria and typhoid became common. The Red Cross was the main relief, but they were overwhelmed, and, as shocking as it sounds, the federal government under Coolidge offered no relief.

As in most disasters, the 1927 flood brought out the worst of humanity. Author John M. Barry wrote of the time, “Their struggle … began as one of man against nature. It became one of man against man. Honor and money collided. White and black collided. Regional and national power structures collided. The collisions shook America.”

Barry, author of the book, “Rising Tide,” gave an interview on NPR in 2005, a month after Hurricane Katrina. One of the questions host Linda Wertheimer asked was why he thought the 1927 flood had not passed into the same sort of legend like the Chicago fire or the San Francisco earthquake. Barry responded, “Well, it’s a good question. I have, you know, only speculative answers. I think one is that it was so big and covered so wide an area, it was a little bit like a dog trying to bite a basketball. People couldn’t get their arms or heads around it. Nobody seemed to step back, at least then, and really look at the whole thing. That’s one of the reasons. And another reason, frankly, may be a certain intellectual prejudice. You know, history was largely written back in the ‘20s, I think, by people who looked askance at the South because of the blatant racism, and they really didn’t care that much about what happened in the area that was most severely hit, which was Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi. And they didn’t write about it.”

The disaster did however bring some positive change, Barry wrote, in what citizens came to expect and demand of their federal government, and how legislators respond.

“Coolidge chose not to run for re-election,” Barry tells, “but that was independent of a flood decision … there were almost 700,000 people being fed by the Red Cross. The federal government did not pay a single penny for the clothing, food or shelter of any one of those 700,000 people. And the American people did not accept this. They felt that it was wrong, and looking at this, I think, created a real change in the way Americans as a people viewed the role of the government’s responsibility toward individuals.”

Sources: Smithsonian, NPR, National Geographic, “Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How it Changed America,” by John M. Barry.

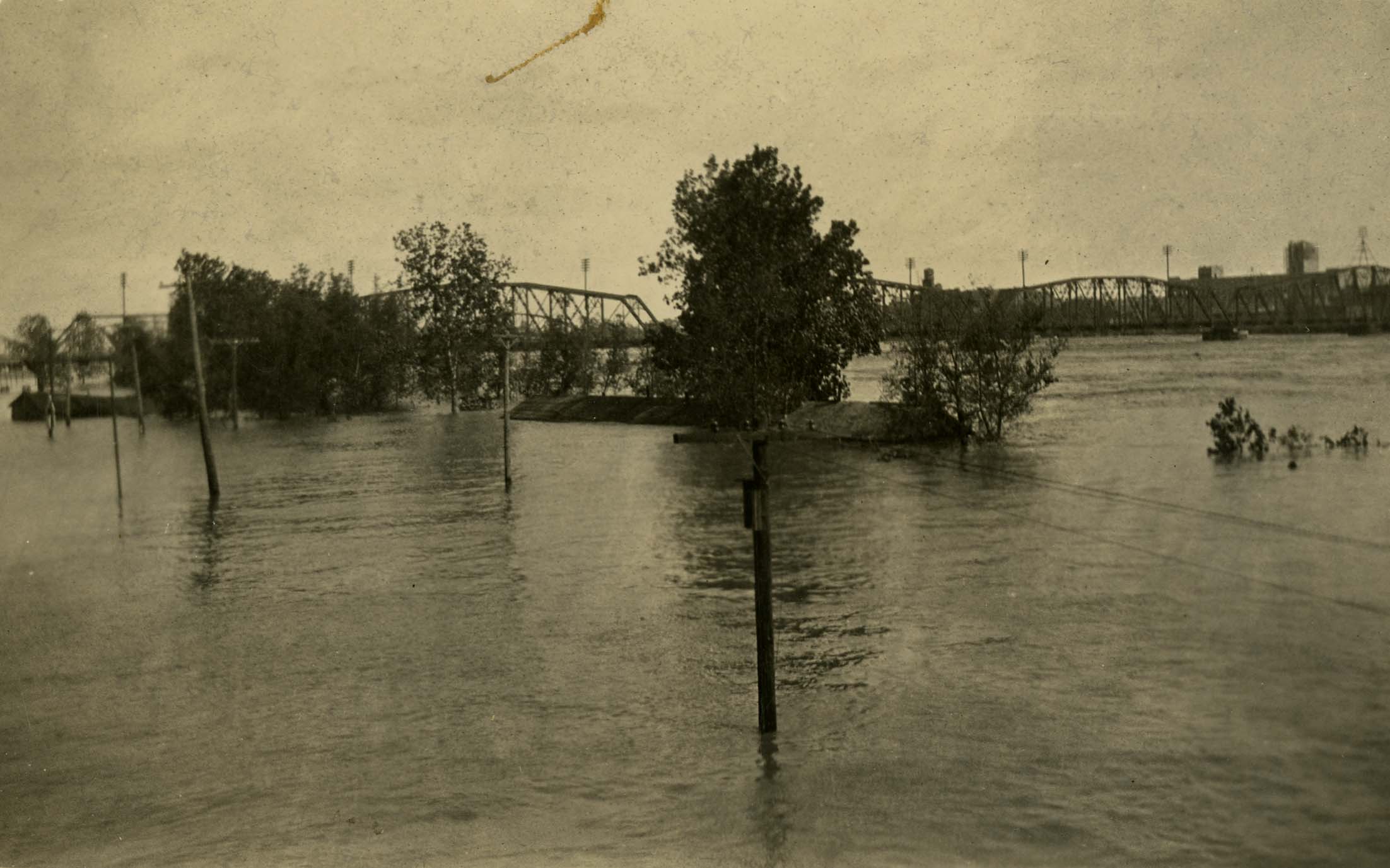

PHOTO CAPTION:

The Mississippi River marks Arkansas’s eastern border, and today is often a beacon for tourism, as seen above. Nearly a century ago, however, the Mississippi was involved in one of the greatest floods seen in the South. Thanks to floodwaters from the Midwest the river grew to a massive width of 60 miles in the Delta in 1927. (Photo courtesy of Arkansas Parks & Tourism)

(Black and white photos courtesy of Arkansas State Archive)