Arkansas’s law deans push diversity, earlier exposure to attract students

July 19-25, 2021

By Dwain Hebda

Combined, Pine Bluff and Osceola, Arkansas, are 585 miles one-way from the University of Arkansas campus in Fayetteville. So, when delegations from the state’s land grant law school traveled to these locales earlier this year, you can bet they had important legal arguments to make.

In fact, they did, though it wasn’t in a courtroom or before a judge and jury. The groups, which included students and faculty, were making an appeal to high schoolers as to the nature and importance of a career in law. All part of the U of A’s attempt to feed a state starved for legal expertise, particularly in and around communities such as these.

“I’ll be transparent and say we are putting much more thinking into recruitment than we once did,” said Margaret Sova McCabe, dean of the University of Arkansas School of Law. “In the past, it’s been easier in Arkansas to think students will automatically come to school here. After the recession, we didn’t slow down as much as some states, but we did slow down. We need to be much more engaged with that early question of why come to law school, what it means to be a lawyer and when you hear ‘rule of law’ what does that means.”

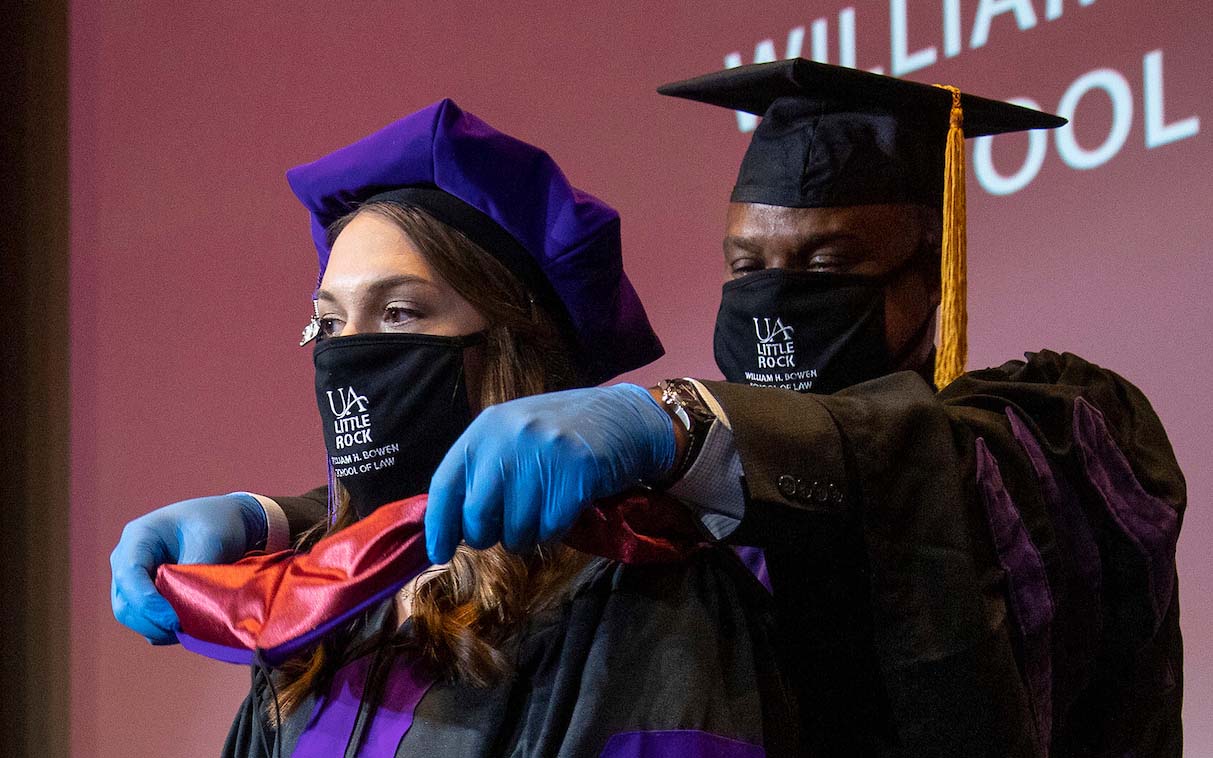

Sova McCabe, who took over as dean in 2018, isn’t alone in her efforts. At UA Little Rock’s William H. Bowen School of Law, the goal is the same as their neighbors to the Northwest.

“We know from studies by the LSAC (Law School Admission Council), which is the organization which administers the LSAT (test), that people who decide to go to law school decide to go to law school well before college,” Theresa Beiner, dean of the UA Little Rock law school. “You need to get students thinking about it early and then that makes a difference in what they end up taking in undergrad, what their focus is on in terms of making sure they get the grades they need and get the LSAT prep they need in order to be great candidates for law school.”

“We’ve just started a partnership with Southwest High School here in Little Rock and we’re hoping to get our students and one of our faculty members in there to discuss what lawyers do and what students need to become a viable candidate for law school, in terms of what they should be thinking about in high school as well as college,” Beiner explained. We’re hoping to be able to coach their trial team down the road as well. We’re looking for ways we can partner with that school to get students interested in law early on.”

Statewide lawyer shortage

Across the state, Arkansas’s attorney numbers severely fall short of need. In the 2020 Profile of the Legal Profession, published by the American Bar Association, Arkansas tied with Arizona and South Carolina for last in the nation in lawyers per capita at just 2.1 attorneys per 1,000 residents.

A closer look showed legal representation wasn’t even that high in many counties, particularly rural Arkansas. In fact, Cleveland County was one of just 54 in the nation to have no resident attorneys while six more counties – Montgomery, Newton, Scott, Calhoun, Fulton and Lafayette – reported fewer than five. Twelve more counties reported attorney headcount of 5 to 9 practicing lawyers within their boundaries, per the report.

Such numbers are nothing particularly new but are nonetheless statistics of which the state’s two law school deans have seen enough. After a 2020 which saw the number of attorneys drop nearly 6 percent – the highest loss of any state in the nation – Arkansas rebounded with 8 percent growth between 2020 and 2021 per ABA statistics, again tops in the nation by nearly 2 to 1 over the second-place state.

Locally, the U of A Bowen Law School had 113 students in its 2019 entering class, 130 in 2020 and Sova McCabe expects about that many in 2021. Bowen welcomed 157 in 2020, roughly the same as the previous year, both of which Beiner said is about 20 more than an average-sized class. Both deans admit, however, that to move the needle meaningfully after years of trending in the wrong direction is a much thornier path to clear, as much impacted by national winds as local efforts.

“I have to go back in time to come full circle,” Sova McCabe said by way of explanation. “The legal education in general, at the great recession, had a 40 percent national contraction in takers and the reason for that was obvious. The great recession really altered the legal hiring market, whether you were a top-ranked school or a school without a rank with a local following.”

“So, there was a slowdown in legal hiring as we ran into the recession, while post-recession tuition and fees didn’t reflect an economic downturn. In fact, I think they went the other direction,” the UA Fayetteville law school dean continued. Therefore, this year is going to be the first year since the recession that we may be back at pre-recession numbers of LSAT-takers.”

Beiner said the reasons for the rebound at many law schools in recent years have also been greatly affected by events of a global nature.

“Like they’re saying nationally, there has been something called a Trump Bump,” she said. “There was a lot of attention on immigration issues at the border and lawyers were at the forefront of a lot of what was going on during the Trump administration. So, there was a renewed interest in law school.

“That, along with the pandemic where people who normally would be graduating and getting jobs were finding it hard to find jobs. If you wanted to go to law school at some point, this seemed like a good time because there weren’t as many available jobs as normal. I think those two things contributed to an increase in enrollment in the last couple of years,” Beiner concluded.

Attracting attorneys to law school is one thing, but there are other challenges as well including attracting diversity. Sova McCabe said women have outnumbered men most years in law school classes in Fayetteville, but acceptable levels of racial diversity have been slower in coming.

“Last year, we were able to achieve nearly 20% diversity for the first time in a few years,” she said. “But if you go back in time, there was an era before the recession where our diversity was higher than that, particularly with Black students. So, we’re in the process of rebuilding.”

“With respect to race, I think Dean Beiner and I are both wanting more diversity in our classrooms because we want diversity in the profession. People should feel comfortable with their lawyer for whatever they need and sometimes that’s a lawyer who understands them in more ways than just what the law says about their situation.”

Beiner added that keeping new attorneys in the state is another priority – especially in rural Arkansas – albeit one law schools have less direct impact on after graduation than say, market forces or quality of life factors.

“People want to go to population centers because there’s more to do, there’s more restaurants, there’s more activities, and there’s potentially more clients in terms of business-type clients,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t significant needs in rural parts of the state, especially for average citizens who need divorces, who need wills and trust work done, who need minor criminal charges taken care of. There’s a lot of work in every county in the state for that type of lawyer, somebody who wants to be a small-firm, practice lawyer.”

One element that both deans said could help in this effort would be state programs that incent new lawyers to go into rural practice. Such incentives already exist for certain health care professionals.

“If I could wave a magic wand, it would be great if the legislature would actually fund scholarships for law students – like they do with doctors – willing to serve in rural parts of the state,” Beiner said. “There’s a real need for lawyers in rural parts of the state and any kind of financial support, whether it be through scholarships or loan forgiveness, that we can give to people who are willing to serve those populations would be great.”

Sova McCabe said in addition to this, rural communities themselves have a role to play in attracting the kind of long-term professional services its residents require.

“I do think we have to think more broadly about community development,” Sova McCabe said. “One example I point to is El Dorado. There’s a community that’s really thought about what it offers to its people and is now a community I could see as being a place where the next generation of fill-in-the-blank professionals would feel like ‘I should go set up shop there.’ They have good venues, they have a nice-sized community, a lot of friendly people and it’s an attractive community.”

“It can’t just be, ‘We’ll incent you to come to a rural community,’ without thinking more broadly about what that person needs for support to be successful and to be a part of rebuilding rural communities. It’s not easy,” she added. “That’s probably the bottom line, it’s not easy to launch people into rural practice. You need to have a community development strategy to plug into.”