COVID-19 highlights health disparities for African Americans, communities of color

August 3-9, 2020

By Daily Record Staff

Almost from the time when the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 was declared a pandemic in early March, anecdotal reports near and far immediately concluded that African Americans and people of color were dying at a higher rate than their white counterparts.

By mid-April, well after COVID-19 was part of American lexicon and local and state government officials began implementing social distancing and shelter-in-place orders, several medical journals had published sufficient data about the fast-spreading virus to draw some startling conclusions.

On April 15, Dr. Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology in the department of medicine at Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute in Chicago, wrote a one-page report in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) predicting that COVID-19 would have a societal effect comparable only to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918.

At the same time, Yancy also raised fresh questions about differences in COVID-19 disease risk and fatality rates across the U.S., noting several media and medical reports that highlighting the health disparities involving COVID-19 in communities of color.

“[A] new concern has arisen – evidence of potentially egregious health care disparities (are) now apparent,” wrote Yancy. “Persons who are African American or black are contracting SARS-CoV-2 at higher rates and are more likely to die. Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man.”

In his one-page JAMA commentary, Yancy also highlighted differences in disease risk and fatality rates across the U.S. in the first two months of the pandemic. For example, more than 50% of COVID-19 cases and nearly 70% of COVID-19 deaths in Chicago involve black individuals, although blacks make up only 30% of the population. Moreover, these deaths are concentrated mostly in just five neighborhoods on the city’s South Side, he said.

In Louisiana, 70.5% of deaths have occurred among black persons, who represent 32.2% of the state’s population. In Michigan, 33% of COVID-19 cases and 40% of deaths have occurred among black individuals, representing 14% of the population. In New York City, this disproportionate burden is validated again in underrepresented minorities, Yancy said, especially blacks and now Hispanics, who have accounted for 28% and 34% of deaths, respectively.

Yancy also mentioned a highly-cited Johns Hopkins University and American Community Survey that indicated that of 131 predominantly black counties in the US, the COVID-19 infection rate is 137.5/100 000 and the death rate is 6.3/100 000.5. This infection rate is more than 3-fold higher than that in predominantly white counties, data from the study shows.

“Moreover, this death rate for predominantly black counties is 6-fold higher than in predominantly white counties. Even though these data are preliminary and further study is warranted, the pattern is irrefutable: underrepresented minorities are developing COVID-19 infection more frequently and dying disproportionately. Do these observations qualify as evident health care disparities?” asked Yancy.

“Yes. The definition of a health care disparity is not simply a difference in health outcomes by race or ethnicity, but a disproportionate difference attributable to variables other than access to care,” Yancy continued. “What is the action plan? It is less an action plan and more of a commitment. A 6-fold increase in the rate of death for African Americans due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed unconscionable. This is a moment of ethical reckoning. The scourge of COVID-19 will end, but health care disparities will persist.”

More recently, the APM Research Lab in its ongoing Color of Coronavirus project monitors how and where COVID-19 mortality is inequitably impacting certain communities. According to the nonpartisan research arm of American Public Media, the coronavirus has claimed more than 141,000 American lives through July 21, 2020. Data about race and ethnicity is available for 91% of these deaths.

“Our latest update reveals continued wide disparities by race, most dramatically for Black and Indigenous Americans. We also now adjust these mortality rates for age, a common and important tool that health researchers use to compare diseases that affect age groups differently,” said APM. “The result? Even larger mortality disparities observed between Black, Indigenous, and other populations of color relative to Whites — with the greatest rise in mortality among Indigenous and Latino Americans, who are the youngest populations of all race groups.”

Phase 3 Clinical Trials Concerns

In the upcoming Phase 3 trials, there are also growing concerns that although Black and Latino people have been three times as likely as white people to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die, volunteers from those groups are less likely to be included in testing despite NIH rules.

In a blog post on May 14, NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins noted growing list of disturbing statistics about how Blacks, Hispanics, tribal communities, and some other racial, ethnic, and disadvantaged socioeconomic groups are bearing the brunt of COVID-19. One of the latest studies comes from a research team that analyzed county-by-county data which highlighted that 22% of U.S. counties that are disproportionately Black accounted for 52% of COVID-19 cases and 58% of COVID-19 deaths.

Collins noted that the NIH, through the Trump administration’s planned Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership, has been developing a collaborative framework for prioritizing vaccine and drug candidates, streamlining clinical trials, coordinating regulatory processes and leveraging assets among all partners to rapidly respond to the COVID-19 and future pandemics. When NIH announced the COVID-19 “fast track” program to find a vaccine in April, Collin said the ongoing clinical trials should be “a part of the whole-of-government, whole-of-America response the Administration has led to beat COVID-19.”

“We hope … we will be in a position to begin testing these vaccines on a large scale, after having some assurances about their safety and efficacy. From our conversation, it sounds like we should be trying to get early access to those vaccines to people at highest risk, including those in communities with the heaviest burden,” Collins said of Phase 3 clinical trials that are now underway. “But how will that be received? There hasn’t always been an easy relationship between researchers, particularly government researchers, and the African-American community.”

Among the current final stage trials in the U.S., the investigative vaccine co-developed by the Cambridge, Mass.-based biotech firm and the NIH is now seeking 30,000 volunteers for its research testing at 89 locations across the U.S. In its Phase 3 SIMPLE-Severe trial that began in late February, Silicon Valley-based Gilead Science Inc. has included an evaluation of the safety and efficacy of remdesivir across different racial and ethnic patient subgroups treated in the U.S. The Silicon Valley-based biopharmaceutical firm said it found that traditionally marginalized racial or ethnic groups treated with remdesivir in this study experienced similar clinical outcomes as the overall patient population in the study.

Recognizing the need to address the impact of COVID-19 and other diseases on communities of color, Gilead and the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine announced on Tuesday (July 28) they were working together to develop a real-time, public-facing and comprehensive health equity data platform.

The tool will provide the ability to collect and study the demographic disparities associated with COVID-19, with the goal of using this data to help create actionable, evidence-based policy changes to attain health equity and ensure that disproportionately impacted communities receive resources and support. The database will also examine comorbidities associated with COVID-19, including asthma, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, obesity, sickle cell anemia and depression.

Gilead and the historically black university (HBCU) and medical school in Atlanta said COVID-19 data demonstrate that the disease disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic minority groups, particularly Black Americans.

“As we have seen, COVID-19 is magnifying inequities that predate the pandemic,” said Daniel Dawes, director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. “Black Americans, Native Americans, Latinx Americans, Asian and Pacific Islander Americans still contend with neighborhoods that are largely devoid of health-sustaining and health-protective resources, and they still contend with the political determinants or drivers that created, perpetuated and exacerbated these health inequities. We are honored to partner with Gilead to address the root causes of health inequities. Our collective effort intends to create systemic policy change and realize more equitable outcomes for all population groups.”

Gilead will initially provide $1 million for the project and also to support the creation of a Black Health Equity Alliance, composed of national thought leaders, community representatives, scholars, researchers and policymakers, which will help coordinate COVID-19 education, training, information exchange and dissemination, and policy analysis.

“The data we are compiling with the Satcher Health Leadership Institute will provide the insight we need to help build a better healthcare system for the Black community,” said Douglas Brooks, executive director at Community Engagement at Gilead Sciences. “At the core, the work we do at Gilead is being on the frontlines where the need is greatest, as we have done in HIV and hepatitis C in communities across the country. There are many hurdles in the American healthcare system for the Black community to access care and without data like this, we will be having the same conversation when the next pandemic strikes.”

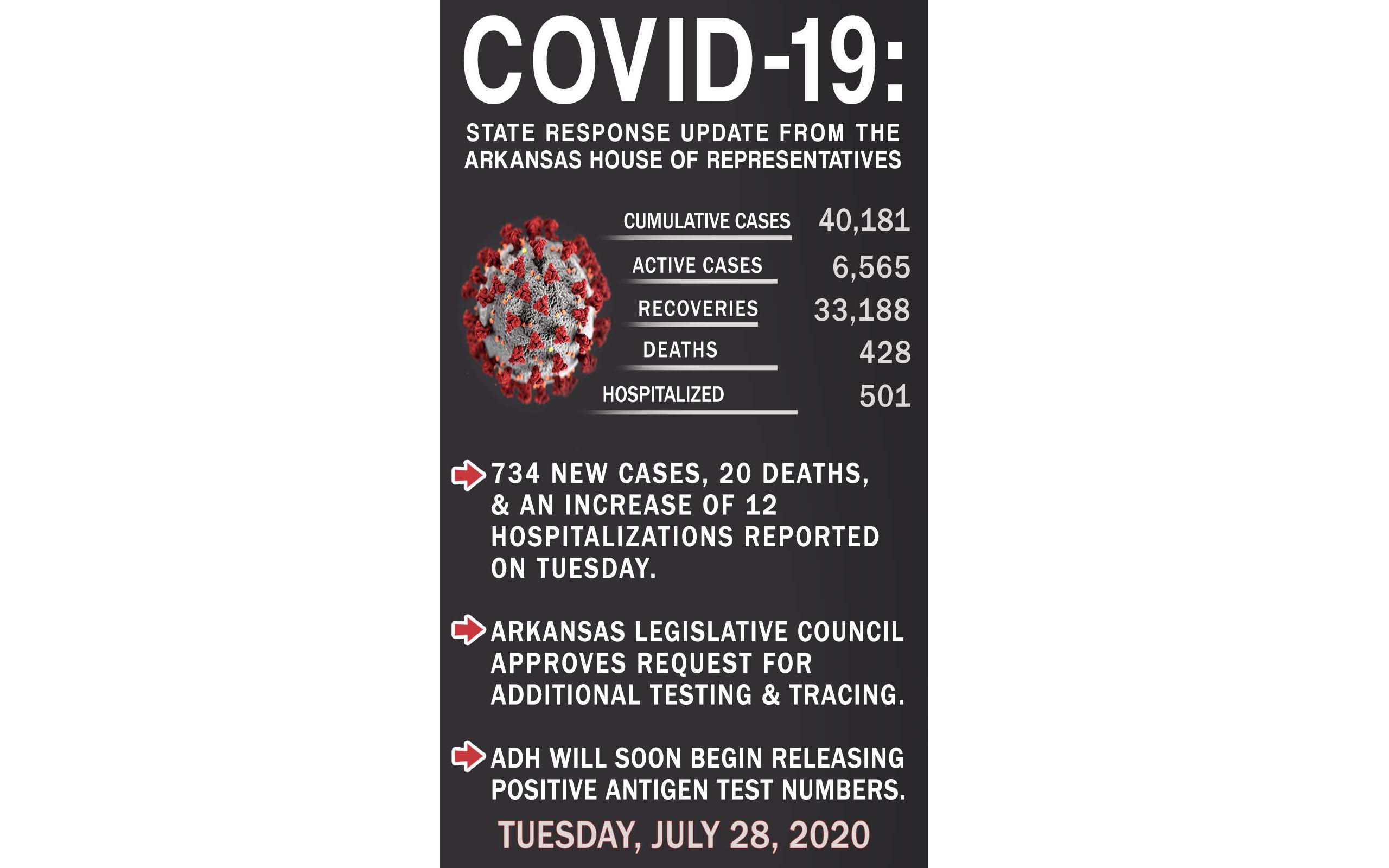

In Arkansas, the Arkansas Legislative Council (ALC) on Tuesday voted in favor of directing $16 million in federal CARES Act funding for additional contact tracing statewide as COVID-19 deaths across the state hit 20, the highest one-day spike since the first positive coronavirus case on March 11.

The ALC, a bicameral committee of House and Senate members that acts on behalf of the Arkansas General Assembly in between legislative sessions, also approved $7 million in federal funds to be directed to testing and tracing in minority communities in Northwest Arkansas. Last week, the powerful legislative committee refused to suspend rules and take up the measure to consider the state Department of Health’s proposal to provide additional funding to test Hispanic and Marshallese populations that have seen a spike in COVID-19 cases and deaths in Northwest Arkansas.