Depression-Era White River culture and the girl avenger

June 4-10, 2018

By Jay Edwards

In January of 1931, a man named Jack Worls sat in a DeWitt, Ark. courtroom, waiting for the verdict that was only moments away, a decision that would tell his fate. He never heard the foreman’s voice pronouncing him guilty or not, because an 18 year-old girl named Helen Ruth Spence had already decided for herself that Worls was guilty, and carried out her own justice from the barrel of her smoking .45. What was the end for Worls, began a short life of infamy for Spence, who replied when asked why she’d done it, “He killed my daddy.”

Spence was born on a houseboat on the White River, one of the “river people” or “river rats” as some of the less sympathetic “dry-landers” referred to them. There is some discrepancy about the year of her birth, with some saying it was 1912, while other reports have it as 1916.

She left school for good after the ninth grade and married a local boy named Buster Eaton, whose future was in making moonshine. But the marriage didn’t last and Helen Eaton went back to her maiden name and to her daddy, Cicero Spence, and the houseboat where he lived with his second wife, Ada. Helen’s mother, Ellen, was deceased.

One day, in early January of 1931, Cicero and Ada went off for a day of fishing. Jack Worls joined them. Somewhere along the way, Worls shot and killed Cicero and then raped and beat his wife. Ada died soon after in a Memphis hospital. Worls was quickly apprehended and time wasn’t wasted on picking a jury. But young Helen had something else in mind.

Like many other parts of rural America in the early decades of the 19th Century, the people of the White River in Arkansas County lived by a different sets of rules. And while these folks weren’t exempt from constitutional laws, factors such as resources, time and prejudice gave “river people” more motivation and opportunities for self-legislation and the carrying out of their own swift brand of justice. In fact, when he was killed, Cicero Spence was only days away himself from being arrested for murder.

In an article on the river people in April 2006 in the Arkansas Times, reporters gave a timeline of murders from the era.

“1887, Joe Smith killed Jim Turner. Mrs. Keness was supposed to have killed Bob Vann. Arthur Bird killed Fread Wilks. Joe Smith killed Martin Billingsley.”

“1893, June 22, Jerdon Phillips was hung in DeWitt by the law. The only one ever in Arkansas County. Joe Smith did the job.”

“1893, Jack Thompson killed Ben Petis.”

“1894, Welby Parker killed Walter Ballard through a mistake. Bob White killed John Gray and John Berton at the same time.”

Jump ahead 42 years, 50 killings, numerous drownings in the 1897 Little Garrett Flood and a 1906 bank holdup to the Great Depression, when lawlessness prevailed all across the South and Midwest:

“1936, Roberts killed Mr. Binswinger. Cecil Lacotts was killed by the law. Jessie Eason was by Fishlowe. Robert Bostick killed a negro woman on the Arkansas River. Peat Duglas and Harry Simmons killed Johnson Moss. Joe McCowen killed Joe Gordon. Dan Gordon was killed by unknown parties.”

So killing folks, while against the law and for the most part frowned upon, may not have always been the last resort.

Helen Spence became instantly notorious. With her youth, good looks and seemingly cold-heartedness, reports of the courtroom killing went national, appearing in publications that included The New York Times and Washington Post. People from all over were immediately sympathetic to the young woman who had avenged her father’s and stepmother’s deaths.

She was convicted of manslaughter on October 8, 1932. But due in large part to a public who rallied to her cause, she was paroled and freed on June 10, 1933.

ANOTHER KILLING

In February of 1932, thirteen months after the shooting of Jack Worls, the body of Jim Bohots was discovered in an area known as a “trysting spot” by locals in Arkansas County. He’d been shot to death.

Bohots owned a DeWitt café, where he had been known from time to time to harass the waitresses with unwanted advances. One in particular regularly fancied his eye. Her name was Helen Spence. When authorities called her in for questioning she convinced them she wasn’t involved in Bohots’ death, and they let her go.

On June 15, five days after she was released from jail for the murder of Worls, Spence walked into a Little Rock police station and confessed to a detective that she in fact had killed Bohots. She claimed he kept insisting he meet with her after work and she finally did. They drove to the remote spot where she said he assaulted her, so she shot him, reportedly with his own gun.

“I felt like I had to kill him,” she was quoted as saying.

With a second killing on her young resume, public sympathy quickly waned. Spence was sentenced to ten years hard labor at the State Farm for Women in Jacksonville, where the warden of the women regularly transported inmates to Memphis for prostitution. But Spence had no intentions of staying in jail, and began planning her escape. She was an adept seamstress and began sewing the cafeteria’s checkered napkins inside her uniform. At the next Memphis rendezvous, she asked to use the restroom, and once inside she turned her uniform inside out and walked away unnoticed. But they caught up with her soon after.

From September to November 1933, Spence would escape three times, only to be captured and punished by twenty lashes with a leather strap known as the “blacksnake.”

In December of that same year, Lee Cazort, the Arkansas Lieutenant Governor, directed that Spence be sent to the State Hospital for observation, but she was deemed sane by the doctor and returned to jail.

On July 10, 1934, she made her final escape. The assistant superintendent, V.O. Brockman sent for one of the prison trustees, Frank Martin, who was a convicted murderer himself, and the pair went looking for Spence. They found her not long after, walking by herself down a country road. Martin wasted no time and shot and killed the famous river girl from Arkansas County. Both men were charged with murder but later acquitted. Martin was later paroled.

Newspapers said Spence was laid to rest at St. Charles next to her father. But others say that some locals stole her body from the funeral home the night before she was to be buried, and lay her in an unmarked grave, where they supposedly planted a cedar tree to mark the spot.

This past April 5, a celebration service was held and a new gravestone was placed in the St. Charles Cemetery in Arkansas County, in memory of Helen Ruth Spence.

The girl, loved by the river people of the Arkansas Delta, is the subject of the book “Daughter of the White River,” by Arkansas author Denise White Parkinson (History Press, 2013). Her grave received the memorial foot stone, courtesy of Arkansas philanthropist Dorothy Morris of the Morris Foundation.

As for Frank Martin, he made the mistake of returning to DeWitt, where he bragged about killing Spence. According to one of her friends from childhood, L.C. Brown, Martin “walked into the grocery store to buy a loaf of bread. The lady sold him a different loaf – told him it was just as good, and cost less. Frank Martin ate dinner that night and never woke up the next morning … It was always said that ‘the river got him.’”

Sources: Stuttgart Daily Leader, Arkansas Times, Pine Bluff Commercial, The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

PHOTO 1:

An aerial view of the White River, which spans 720-miles and travels through 75 Arkansas counties. Helen Ruth Spence considered the body of water her home. (Photo courtesy of Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism)

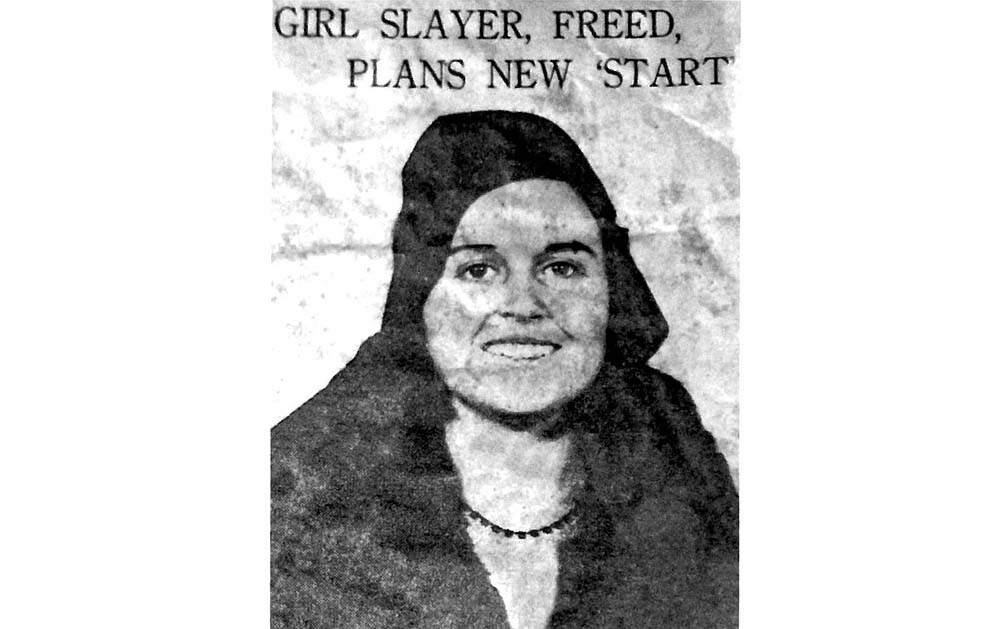

PHOTO 2:

A flyer denoting Spence’s freedom after killing Jack Worls.

PHOTO 3:

Arkansas author Denise White Parkinson chronicles Spence’s life in her book: “Daughter of the White River.”