From England to Hot Springs, the life of a gangster

March 4-10, 2019

By Jay Edwards

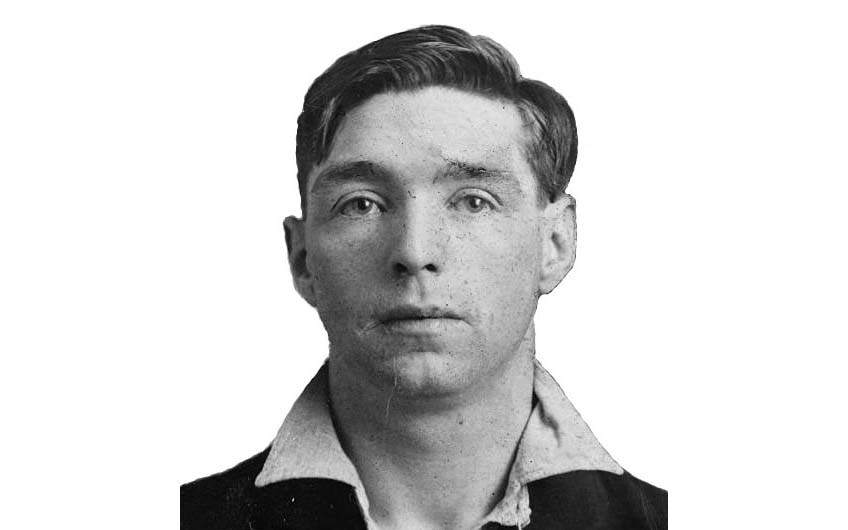

The story of how one of New York City’s most infamous gangsters came to rest in Greenwood Cemetery in Hot Springs, Arkansas, begins in Leeds, England, in the county of Yorkshire, on Dec. 18, 1891. That was when Owen Vincent Madden came into the world.

His mother and father were immigrants from Ireland, who had made the journey across the Irish Sea to escape the effects of “The Great Hunger,” more commonly referred to as the Potato Famine, the great scourge that began in 1845 and eventually reduced Ireland’s population by more than 25 percent.

The Madden’s migrated to what they were sure would be a better life in England, but once there found themselves facing new challenges and hardships common to many of Great Britain’s less fortunate.

After the birth of Owen, Francis moved the family to Liverpool, searching for work. His longer-term dream was to one day migrate again, across the Atlantic to America, where promises of opportunity gave hope to Europe’s poor.

That vision became reality by 1902, when Owen and his two siblings left Liverpool for Manhattan, to join their mother, who had arrived the year before. Some stories say Francis died just before he himself planned to go, and some say he just never went.

Owen, now known as Owney, was ten years old when he first roamed the streets of “Hell’s Kitchen,” the west Manhattan neighborhood that started forming in the southern part of the 22nd Ward in the mid-19th century. Irish immigrants – mostly refugees from the Great Famine – found work on the docks and railroad along the Hudson River and established shantytowns there.

There are varying theories on the origin of the infamous neighborhood’s name. The earliest use of the phrase is actually attributed to Davy Crocket, in a comment he made about the Irish slum in Manhattan, known as Five Points:

“In my part of the country, when you meet an Irishman, you find a first-rate gentleman; but these are worse than savages; they are too mean to swab hell’s kitchen.”

But the most likely version traces it to the story of “Dutch Fred the Cop,” a veteran policeman, who with his rookie partner, was watching a small riot on West 39th Street near Tenth Avenue. The rookie is supposed to have said, “This place is hell itself,” to which Fred replied, “Hell’s a mild climate. This is Hell’s Kitchen.”

What is known for certain was that it was the perfect climate for a young Irish immigrant who longed to make a name for himself.

At the start of the 20th century, Hell’s Kitchen was controlled by gangs, including the violent Gopher Gang led by One Lung Curran.

Madden joined the Gophers and soon gained a reputation as a fierce fighter, eventually getting nicknamed “Owney the Killer” for shooting down a member of an Italian gang in the streets, after which he shouted: “I’m Owney Madden, 10th Avenue!”

By the time he reached his 18th year he was famous and feared. In “The Gangs of New York,” Herbert Asbury wrote of Madden:

“He was but (eighteen) when he assumed command of one of the Gopher factions, and had scarcely passed his twenty-third birthday, with five murders chalked against him by the police, when he was imprisoned. He was a crack shot with a revolver, and an accomplished artist with a sling-shot, a blackjack, and a pair of brass knuckles, not to mention a piece of lead pipe wrapped in a newspaper, always a favorite weapon of the thug. The police regarded him as a typical gangster of his time – crafty, cruel, bold, and lazy. Until he went to jail he had never worked a day in his life, and often boasted that he never would.”

That road to prison for Madden began on Nov. 6, 1914, when members of a rival gang got the opportunity they’d been waiting on. Madden arrived one night at the Arbor Dance Hall on Fifty-Second Street near Seventh Avenue. He was alone and drunk. He marched in and went to the middle of the dance floor and stood there defiantly, scowling at the crowd, many of whom began looking for the nearest exit.

“Go on and have your fun!” Madden shouted. “I won’t bump anybody off tonight. I don’t want to spoil youse guy’s party.”

Then he went up to the balcony, where he sat and drank whiskey for the next few hours. The appearance of an attractive girl, along with the liquor, lowered his guard, and suddenly he was surrounded by eleven members of the Hudson Duster’s, a Gopher rival gang. Never one to back down, Madden stood and faced his assailants.

“Come on youse guys!” he shouted. “Youse wouldn’t shoot nobody! Who did youse ever bump off?”

But the Dusters did shoot, and they hit Madden six times.

Later in the hospital he was asked by police who’d done it. “Nothin’ doin,’” the gangster replied. “The boys’ll get ‘em. It’s nobody’s business but mine who put these slugs into me.” In less than a week, three of his attackers were dead.

While Madden lay mending in the hospital, Gopher gang member “Little Patsy Doyle,” decided he should be running things and told the gang that Madden wouldn’t be back. But Madden wasn’t in total agreement with Doyle, and when he left the hospital a small war began. It stopped after Madden convinced Doyle’s supporters he was a stool pigeon. After Doyle lost his muscle, Madden planned his murder.

On Nov. 28, 1914, just over three weeks after Madden had been shot six times and left for dead, Gopher girl Margaret Everdeane met with Freda Horner and “Willie the Sailor” at the Ottner Brothers’ bar at Forty-first Street and Eighth Avenue. Everdeane called Doyle and told him his old girlfriend Freda was interested in getting back together. Doyle bought it and showed up at the bar to meet Freda, but instead met two of Madden’s men, who shot Patsy. He staggered out of the bar and fell dead on a doorstep.

Police arrested the two women and “Willie the Sailor,” who all testified Madden had been behind the hit. Of all the 57 crimes charged against him, this would be his first conviction. His sentence was ten to twenty years in Sing Sing.

Nine years later he walked out a free man. By the end of the decade he would be a millionaire, thanks in large part to prohibition. Before the age of 40 he was kingpin of an underworld empire that included real estate, boxing, gambling, bootlegging, breweries, and entertainment.

Over the next few years things changed a great deal. President Roosevelt was committed to ending organized crime and prohibition was repealed, which greatly cut into the mob’s bottom line. Madden was having health problems from his many past gunshots and after another stint in Sing Sing for parole violations, he decided to retire in Hot Springs, where certain business interests benefitted mightily by a corrupt city government.

It was sort of like old times for Madden, who was soon furnishing the wire service that brought racing results to bookmakers. He was mostly quiet however, until 1940 when he came to own a controlling interest in the Southern Club, on Central Avenue, where gangster heads like Frank Costello, Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky visited him regularly.

After his move to Hot Springs Madden married Agnes Demby, the daughter of a local postmaster. They moved into a small home on West Grand Avenue.

In 1961 Madden was subpoenaed to testify before the Senate Committee on Organized Crime under United States Senator John McClellan from Arkansas (“the rackets committee”). During the hearing Madden repeatedly invoked the Fifth Amendment.

In 1964 the state began shutting down illegal gambling in Hot Springs, which the feds had named the site of the largest illegal gambling operation in the U.S.

A year later, on April 24, 1965, Owen Vincent “Owney” Madden died of emphysema and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.