History-making Pulaski County sheriff takes department through once-in-lifetime challenges

October 11-17, 2021

By Dwain Hebda

The old saying, “There’s a new sheriff in town,” has never been more apt than in describing Eric Higgins who was sworn into the role in 2019. From that day, Higgins has shown he’s unlike anything the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Department has ever seen, from the well-reported fact that he’s the first Black sheriff in the department’s history, to beliefs and values that run far deeper than skin tone.

Now, with remarkable times calling for remarkable measures, Higgins’ frank, outsider perspective has proven to be just what’s been needed to steer the department through the COVID-19 pandemic and the dual tides facing law enforcement today: national waves of anti-police sentiment and the undertow of racial inequity, both equally powerful and dangerous.

“We have to work hard to build our relationship in the community. We have failed as law enforcement a number of times,” said Higgins. “I think that the first step is to acknowledge the history of law enforcement, the reality. When we talk about police officers doing patrolling, preventative patrol, the history of preventative patrol comes from patrolling for runaway slaves. When you look at segregation and the Jim Crow laws and all of that, while law enforcement didn’t pass those laws, we enforced those laws. And that tradition is passed on from one generation of officers to the next.

“The majority of officers are trying to do a really good job and they’re sacrificing and they’re serving the community. But some of them are not. You have good people who don’t make good officers because they can’t handle the job and what we ask our officers or deputies to do and deal with. Then you have good officers who make egregious mistakes and you have to separate them from the agency,” continued Pulaski County’s top law enforcement officer.

“The problem our community has with law enforcement, it is not that they expect us to be perfect, it is that they expect us to be held accountable. We have to acknowledge that and we have to hold each other accountable,” he said.

Higgins said backlash from the department’s early move to amend policy banning chokeholds and compelling intervention of the same is a perfect example of the entrenched attitudes that still exist in many areas of law enforcement.

“It’s hard to believe how much resistance I saw when I talked to other police officials. Their response was, ‘We don’t have anybody like that working for us, it’s not necessary [to change policy], there’s already laws in place.’ And yes there are. But it’s not enough,” he said.

“That’s why there are laws that mandate that every police agency in Arkansas does training on diversity, bias training and things like that. It shouldn’t be necessary, but it is,” added Higgins. “We have to be sensitive to what’s going on in the community, of our actions and we have to implement policies and procedures that address that. I’m not naive enough to believe that you implement a policy and everything’s fine, but it does point out to people their responsibility.”

Higgins’ leadership during the COVID-19 crisis has been similarly resolute. The department employs more than 500, the majority of which manage a county detention center that holds in excess of 1,200 beds and processes more than 20,000 individuals annually. Introducing a highly contagious virus into this environment presents potentially disastrous outcomes.

Instead, the department was proactive, cancelling live visits nearly a month before the state Department of Correction. Even today, live visits are limited to an inmate’s attorney or other special circumstances, while families can maintain contact via a video system that went live a week after in-person visits were suspended.

Given the revolving door of new inmates, it’s improbable to avoid COVID-19 entirely as some come in already infected. Higgins and his team crafted a system of personnel management that identified these individuals and helped prevent widespread infections in lockup.

“We designated isolation units,” he said. “We have two units, one for those who may have been exposed to COVID or say they’re positive or have been in the hospital, and another unit for everyone else who came in. We isolate them for 14 days before they go into our regular unit pod.”

“We work with our medical contractor to bring in CNAs to check everyone coming through the door, including staff. When other agencies make an arrest and come to the detention center, before they walk into the building we check the temperature and pulse of everyone. We require masks; when masks were just recommended, we mandated masks throughout the facility.”

The facility also limits the number of inmates out of their cells at a time for exercise, maintaining the same 10 individuals per group. Keeping the facility as safe as possible wasn’t easy; early on, the department couldn’t get its hands on enough masks and once, when Higgins sought to test all in the facility, he was told the state health department didn’t have enough tests to accomplish it. He found a work-around, and no positive tests were reported, to the department’s credit.

As the vaccines became available, Higgins made sure anyone who wanted it could get it. Policy doesn’t permit forced vaccinations of inmates or mandatory vaccinations for staff, yet nearly 700 individuals received the shot while in the detention center. Moreover, if an inmate is exposed to a COVID-positive individual prior to release, Higgins made sure discharge procedures included information about community health resources in the event they developed symptoms.

If that all sounds like a far cry from traditional jail operations, it should. But to Higgins’ thinking, it should be closer to the norm of what society expects out of such facilities and law enforcement in general.

“We’re dealing with people’s perceptions of offenders or criminals where we just want to punish them. Society says punish them,” he said. “I’m all for people being held accountable for their actions. I have no problem with that. But we can’t just lock them up. We have to look at trying to help people and to have an understanding of criminal behavior and what leads to criminal behavior.”

Higgins said some outdated mindsets are counterproductive to the point of hypocrisy. People are all for extra effort and expenditure during COVID-19, but the same cannot traditionally be said for the drug pandemic that has been ongoing for generations and which has done far more to threaten public safety than the virus. He’s seen progress in the arena of public opinion on addiction and that awareness generally leads to greater resources, such as the addiction programs he now offers in the detention center. But more is needed, such as the 60-plus deputies he’d hire tomorrow, if he could.

“Let’s take crack cocaine; our response to crack cocaine was, it is so dangerous, it is so addictive people will steal from their families. The only solution is to lock them up. We’re talking about crack babies and we’re demonizing addiction,” he said. “Then when the meth issue really started pushing and people were stealing from their families, we need to lock them up but let’s provide some type of treatment program.”

“When the opiate epidemic hit, all of a sudden this is a different kind of addiction and we need to start suing pharmaceutical companies. Well, addiction is addiction and it’s a matter of what you get exposed to, whether it’s taking painkillers or drinking alcohol or trying crack, or trying meth, or anything else,” Higgins explained.

The Pulaski County sheriff admitted some of the new understanding comes with the fact opioid addiction, like alcohol, reaches into rich neighborhoods on a scale that crack and meth never did. But, he said, he’ll take the awareness and empathy wherever he can get it, chalking the rest up to human nature.

“There are individuals who care about all people but speaking broadly, once I’m affected personally, once I see that I can become a victim of this, then I’m more concerned,” he said. “If burglaries are happening in another neighborhood, I may not want burglaries to happen, but I’m not as concerned as when they happen in my neighborhood. Then it’s, ‘What is law enforcement doing?’

“We have to touch people’s minds and help them with the data to show that this is an issue for society and this is a way to address this issue. But then we have to touch your heart and make you care about it. I think that’s so important. And, I think we have a better opportunity now than we did before to be able to look at addiction as a problem worth addressing regardless of what the addiction is. We can’t arrest our way out of this; I think we’re at a better place now than we were 15 or 20 years ago.”

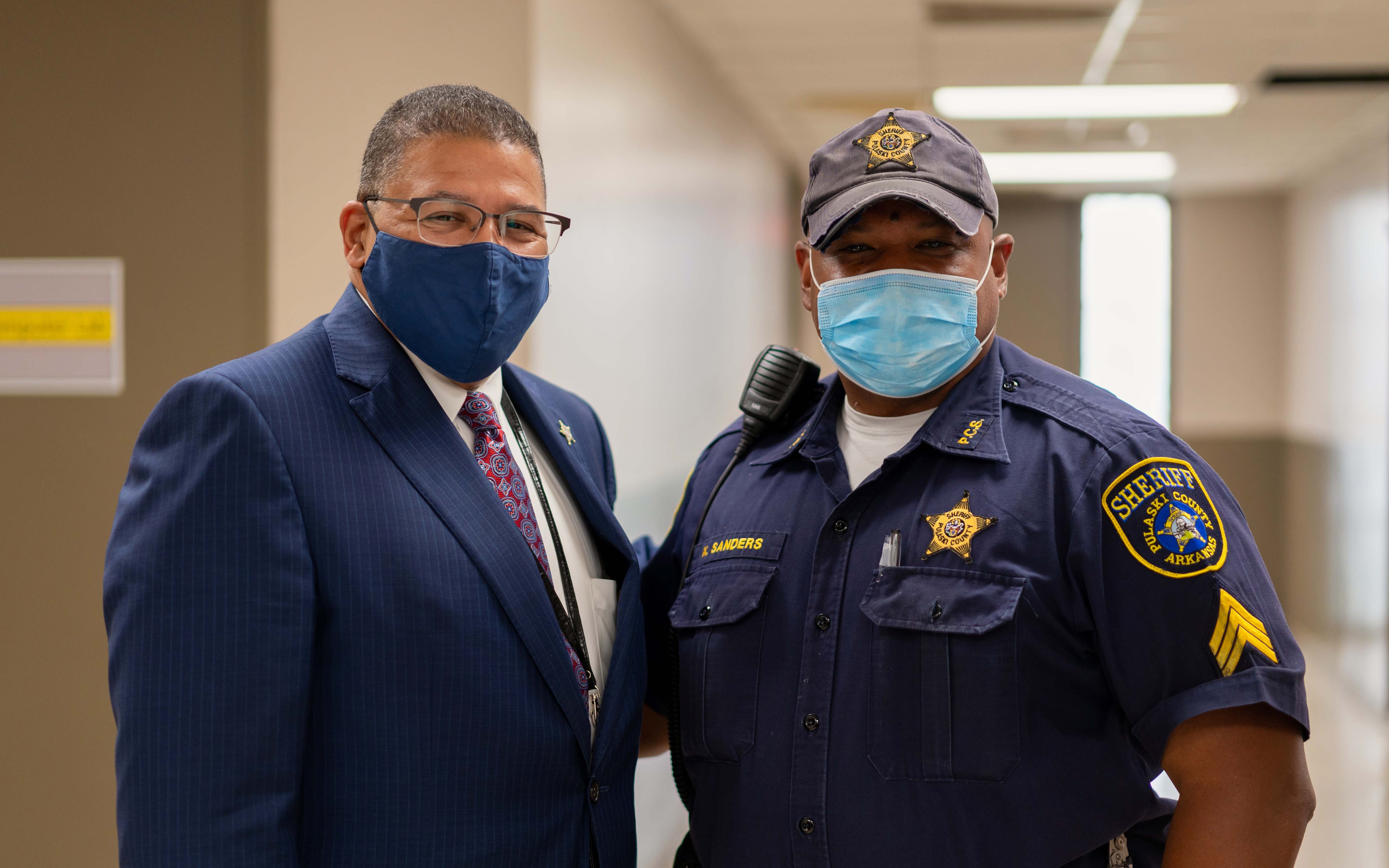

PHOTO CAPTIONS: (Photos by Joseph Crew)

Pulaski County’s first Black sheriff steers department through COVID-19 pandemic, racial inequality discussion. Pulaski County Sheriff Eric Higgins looks over paperwork at his office at 2900 S. Woodrow in Little Rock. Higgins' work involves overseeing all operations at the Pulaski County Regional Detention Facility, which has over 1,500 inmates.