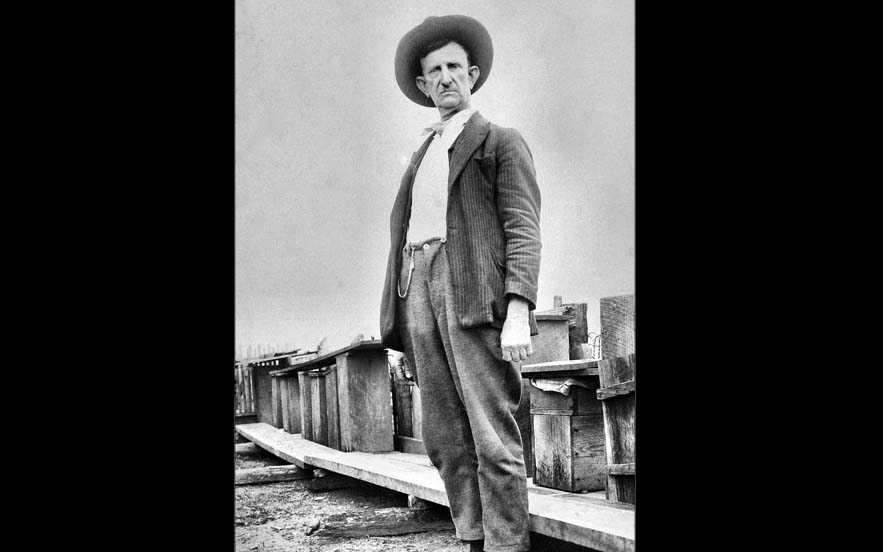

John Huddleston and his crater of diamonds

August 5-11, 2019

By Jay Edwards

It was more than a half century ago when Governor Win Rockefeller signed Act 128, designating the diamond as the state gem, a measure which came more than a half century after the first diamond was discovered by a farmer on his land in Pike County.

John Wesley Huddleston and his wife Sarah had decided, after much thought on the matter, to purchase land in Pike County, where his family had lived for generations. Much like his father and uncles, Huddleston appreciated the value of owning land, and as a reporter who interviewed him later noted, “he saw in it the source of all wealth.”

He had had his eye on a 243-acre tract on the outskirts of town for a while, and bought the property in 1905. One story goes that Huddleston’s interest in the large tract was sparked after a geologist for the state came to the area, first in the late 1880s and then again after the turn of the century. Both times he hired Huddleston as a guide, who watched the geologist carefully as he located and studied small rocks and crystals.

Most reports about the first diamond discovery by Huddleston place the date close to Aug. 1, 1906. He was said to have been searching for copper and iron when he noticed a glimmering stone among the small brown and black rocks surrounding it. Later that day, as he rode his horse towards town, he spotted another crystal laying along the dirt road. When he got to town he showed his discoveries to a bank teller, who supposedly offered fifty cents for the two stones. Huddleston declined the offer, taking them next to Joseph Pinnix, a local lawyer. Pinnix recommended that he send them to Charles Stifft, a Little Rock jeweler, to get an appraisal, which Huddleston did. Stifft confirmed the gems were real, one weighing in at 2.625 carats and the other, 1.6.

His interest more than piqued, Stifft and his son-in-law, Albert Cohn, visited Huddleston’s property a few weeks later. They offered him an option to buy his land based on future discoveries. Huddleston turned them down.

The two did not stop there, partnering up with Sam Reyburn, a Little Rock attorney and the president of Union Trust Company, and the three continued with efforts to purchase Huddleston’s land. The first offer was $360 for an option on the 243 acres, with a purchase price of $36,000 if they decided to exercise their option. They had also included Pinnix in on the deal, who turned out to be instrumental in convincing Huddleston, and Sarah, to finally agree to the terms.

The contract was structured so that Huddleston could continue to search for diamonds, stating, “We further agree, as may suit our convenience, to continue the prospecting of said land, agreeing to turn over to said Sam W. Reyburn, as Trustee, any and all minerals or stones of whatever nature we may find, to be held in trust to go to him in case he exercises the option or to be returned to us in case the said Sam W. Reyburn fails to exercise said option.” On Jan. 9,1907, the Nashville News reported, “J. W. Huddleston, on whose land the diamonds were first found, has found a total of fifteen to date, many of them being splendid stones.” By March 9 a total of 33 diamonds had been found, all but a few by Huddleston.

The option was exercised and Huddleston became known as “Diamond John,” and he and Sarah and their large family moved to Arkadelphia, where they began living the ‘good life.’

Sarah died ten years later, on Dec. 19, 1917. Huddleston sold the Arkadelphia home a year later, returning to Murfreesboro with daughter Delia.

Near the end of 1920, a reporter from the Arkansas Gazette called on Huddleston and wrote that he found him still “a wealthy man, as wealth goes in this remote region,” a man who had “fared better than anyone else engaged in the [diamond-mining] enterprise.”

But just a year later, “Diamond” John, seemed to have lost all his sense when he married a “blonde carnival girl he met in Arkadelphia.” They married on Dec. 29, 1921. He was 59 and she was 19. He did have the good judgement to deed beforehand much of his properties to his daughters, who were all older than his new bride, as he knew marriage would give common-law rights of dower and homestead upon the new wife, giving her joint control of all properties during his lifetime as well as a share of the estate afterwards.

After the wedding, Lizzie – as she was called – hung around less than two weeks before taking off. She returned nearly a year later and stayed about eight months before leaving for good. The marriage was annulled with no contest from Lizzie.

This was in 1924. Later in the year, publisher and editor Tom Shiras of the Baxter Bulletin in Mountain Home journeyed to Murfreesboro to find out more about Huddleston and his 1906 discovery.

“I went to Murfreesboro especially for this interview,” Shiras wrote later. “Walter Mauney of Murfreesboro, who has been associated with diamond mining in the Arkansas field since it started, went with me up to John’s white cottage that morning. There was a comfortable bench before the big fireplace, and we all sat down and lighted our pipes and started to talk. I caught a true picture of John Huddleston that day.

The Ozarks [mountains] have developed the same type of hardy prospectors who first discovered most of the big mines in the West. John Huddleston was of this type. He was not an educated man, but had plenty of practical sense and a determination to do what he thought should be done.”

One of the prospectors for the Arkansas Diamond Company that same year was a man named Wesley Oley Basham. As he dug one afternoon, he tugged on something large and shouted out, “There’s a biggun’ coming!” What Basham found was a diamond weighing 40.23 carats (a little over 8 grams). It remains to this day the largest diamond ever found in the U.S., and was given the name, “Uncle Sam,” after Basham’s nickname. It was later cut down to 12.42 carat and sold for $150,000 in 1971 (about $800,000 today).

The “Uncle Sam” was not the last significant diamond to come out of the land John and Sarah Huddleston purchased in 1905. In 1964, “The Star of Murfreesboro” was discovered at the same site, weighing in at 34.25 carats. Then, in 1975 (the land became the Crater of Diamonds State Park in 1972) the 16.37 carat “Amarillo Starlight Diamond,” was found by W. W. Johnson of Amarillo, Texas while he was vacationing at the park with his family. And in 2017, Arkansas teenager Kalel Langford, 14, hit the jackpot when he found a 7.44-carat diamond.

On average, two diamonds are found every day at Crater of Diamonds, and since becoming a state park more than 33,100 diamonds have been found by visitors. Admission to the park is $10 for adults and $6 for kids.

As for “Diamond” John Huddleston, like so many he would struggle through the Great Depression, when his land became more of a tax burden than an asset. By 1934, he had transferred all properties except his home in Murfreesboro to family members and Pinnix. To supplement occasional farming, he started a business at his place on Kelly Street, buying and selling used goods. On Oct. 1, 1936, he began drawing his social security of ten dollars a month.

Huddleston died at home on Nov. 12, 1941, after a brief illness. He was buried in Japany Cemetery, a family-owned site by the main road, three miles south of the diamond field. Originally, only a plain stone marked the grave. Then in 1995, relatives and other concerned residents from the area fashioned a headstone of native rock. A stonecutter carved a simple inscription beside the image of a sparkling gem: “‘Diamond’ John Huddleston, 1860–1936.” The dates are being corrected.

Sources: John Huddleston (1862-1941):The Man Behind the Myth of “Diamond John” By Dean Banks (Online edition, 2008); Encyclopedia of Arkansas; Arkansas State Parks; nationalgeographic.com; USA Today.

(All photos courtesy Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism unless otherwise noted)