Legal deserts statewide leave Arkansans thirsty for justice

April 5-11, 2021

By Dwain Hebda

Within the state of Arkansas, one can find a variety of ecosystems – mountains, forests, flatland, swamps. To say nothing of The Natural State’s large swatches of desert, of the legal variety that is.

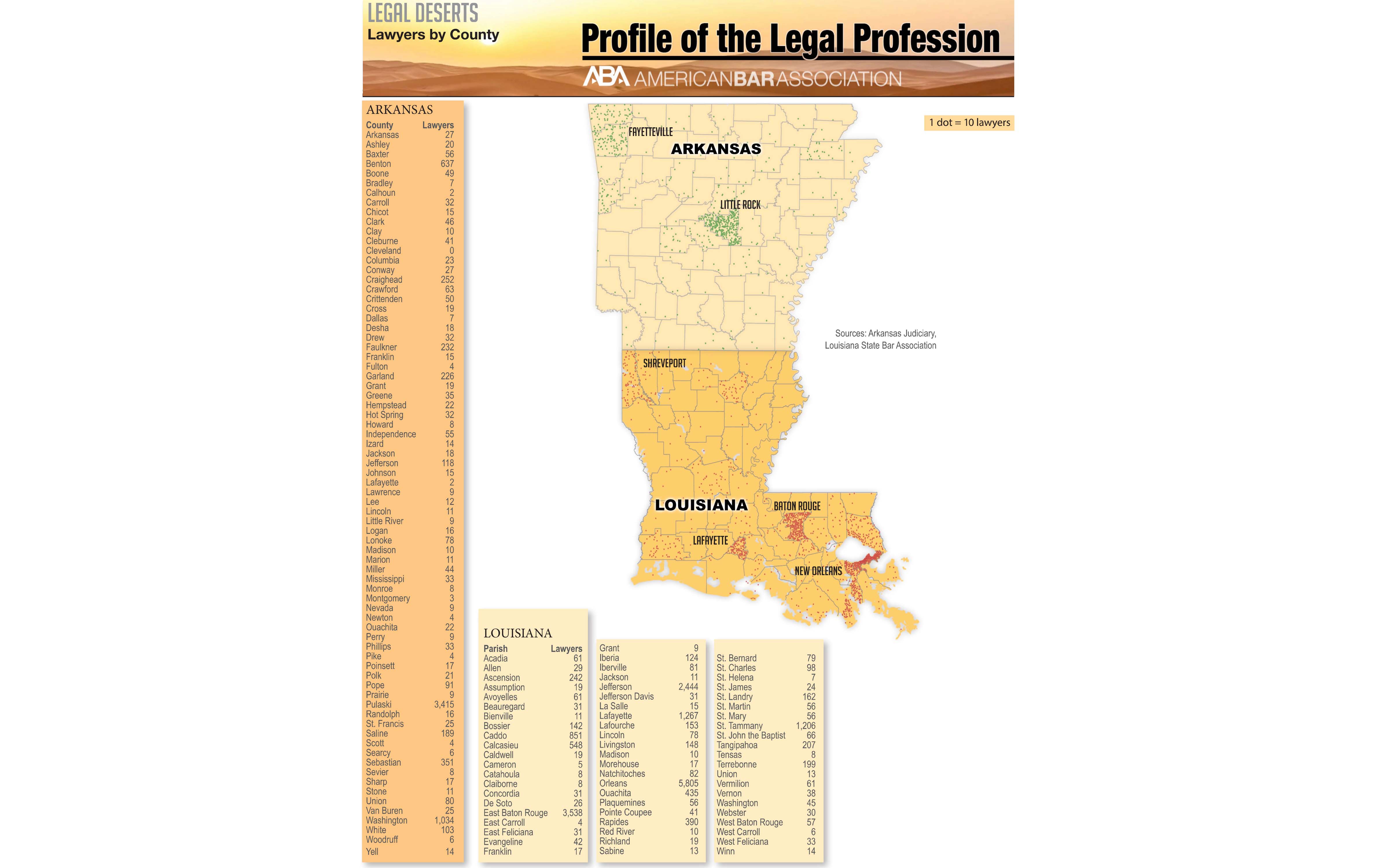

According to the American Bar Association’s 2020 Profile of the Legal Profession report, Arkansas tied for dead last in the nation in lawyers per capita. Boasting just 6,299 attorneys statewide, that works out to 2.1 barristers per 1,000 residents. Arkansas shares this dubious distinction with South Carolina and Arizona.

The distribution of legal expertise in Arkansas follows a familiar nationwide pattern – lawyers clustering in cities and counties with higher populations. To wit, Pulaski County boasts 3,415 lawyers, more than three times that of Washington County in second with 1,034. (Although when you throw in third-place Benton County’s 637 lawyers, you immediately see how quickly the thriving Northwest Arkansas corridor is growing its attorney base.)

On the other end of the spectrum, by contrast, eight Arkansas counties have five attorneys or fewer, including Cleveland County which is one of just 54 counties in the U.S. with zero. An additional 13 Arkansas counties list between 6 and 10 attorneys. As the ABA report stipulates, these are total numbers of attorneys in all types of employment not just those in private practice, further reducing many areas’ legal access.

Arkansas Circuit Court Judge Amy Dunn Johnson is well-acquainted with the legal deserts in Arkansas. For 11 years, she served as executive director of the Arkansas Access to Justice Commission, a nonprofit created at the direction of the Arkansas Supreme Court in December 2003 with the sole objective of providing equal access to justice in civil cases for all Arkansans.

Johnson, who won the 6th Judicial Circuit seat last fall, said thus far the view from the bench hasn’t changed all that much as it pertains to the difficulties many Arkansan’s face to secure legal help.

“We have rural areas in this state in particular that are just extremely underserved,” she said. “I work in domestic relations and there are almost 50,000 cases statewide that get filed in domestic relations matters alone. So, there is a real limitation on what people are able to get in the way of legal representation.”

Johnson said the dearth of attorneys is only part of the challenge of accessible legal representation to all. She said income and growing language barriers are other tall barriers in Arkansas, causing many people to go unserved. And even though resources exist to assist low-income individuals – such as Center for Arkansas Legal Services (CALS) and Legal Aid of Arkansas – people are often unaware of such assistance, a situation made worse by the covid-19 pandemic.

“I feel like a lot of people already fall through the cracks,” she said. “You have people who don’t know about the resources that are available to them. Or they make just a little bit too much money to qualify for legal aid, but still don’t make enough money to pay a lawyer. A lot of Arkansans already fall in that category and our legal aid programs simply don’t have enough resources to meet the demand that’s already out there.”

“There are some good resources that are out there in Arkansas, it’s just kind of a patchwork. The legal aid programs get a lot of calls from people who just need a simple divorce or may have an issue where there’s not an immediate threat to someone’s health or safety. Then, there’s nowhere else really to go in terms of a place that will provide legal representation,” Johnson explained.

Given all these challenges, Johnson said, it is little wonder that the looming legal issues coming out of the pandemic are those that most directly affect people just barely making ends meet. She predicted a tidal wave of issues surrounding evictions and foreclosures in the near term as an example.

“I think the eviction moratorium kicked the can down the road on rent,” she said. “People who’ve been able to successfully put their mortgages in forbearance, they’re still going to have to pay for it. That’s going to be rolled into their mortgage in the future. And unless folks are able to get jobs, a lot of people are already starting out behind the eight ball.”

“I really think that we’re going to see an increase in people who have these kinds of issues because they’ve been going months having difficulty getting access to their unemployment benefits. We’re going to see a real surge in the number of people when all this catches up to everyone,” said the local circuit court judge.

If there was any positive that came out of the pandemic, Johnson said, it was the firm nudge it gave the Arkansas courts to modernize processes to better serve the citizenry and their representation.

“Our court system needs to come up with a more unified and more user-friendly approach,” she said. “The availability of court proceedings through Zoom has actually increased participation over having to take off work and get childcare and find where to park to go to court. As a judge, I plan to continue using Zoom to make things more accessible for people who might otherwise have difficulty physically getting to the courthouse. That’s an area where I’ve seen some really positive change and I’m hopeful that at least with regard to that, our legal system is more accessible.”

“Jury trials are a little bit different animal, but in terms of the day-to-day types of cases that folks have in court with divorces, custody issues, domestic violence, traffic tickets, those kinds of things, people are able to access the courts and attend hearings by Zoom. There have been some lawyers who have been slow to adapt to it but it’s really, I think, revolutionized things. I just hate that it’s taken a pandemic for us to make better use of technology,” Johnson concluded.

Another technological resource that has been in play pre-pandemic are self-help options such as AR.FreeLegalAnswers.org and ARLegalServices.org which provide fact sheets, automated forms and other resources. Johnson said improving and promoting such resources could help in the drive for wider legal access, especially in the preliminary stages of a case.

“Our court system needs to assume the responsibility for being more transparent about how things work and making information about how common processes work,” she said. “When someone files a lawsuit they often don’t know that they now need to go get somebody served and they don’t necessarily know that they need to call to get a hearing scheduled.”

“If our court system as a whole was more transparent to the public about how we work, that would help. There are a lot of folks who do have the wherewithal to be able to navigate and deal with fairly simple legal issues on their own.”

PHOTO CAPTION:

Pulaski County boasts 3,415 lawyers, three times more legal experts than any other county in Arkansas. Washington County in Northwest Arkansas is second with 1,034 attorneys, according to ABA data.

GRAPHIC CAPTION:

Acknowledgement - The Arkansas "snapshot" was part of the American Bar Association’s 2020 Profile of the Legal Profession, an annual ABA publication. This profile offered a look at the legal profession at a fragile moment during the COVID-19 pandemic: July 2020. It offers a statistical look at legal deserts – areas with few lawyers – including the number of lawyers in every U.S. county and maps that show where lawyers are and aren’t.