Little Rock’s Forgotten Legend Part II

December 31 - January 6, 2019

By Kris Rutherford

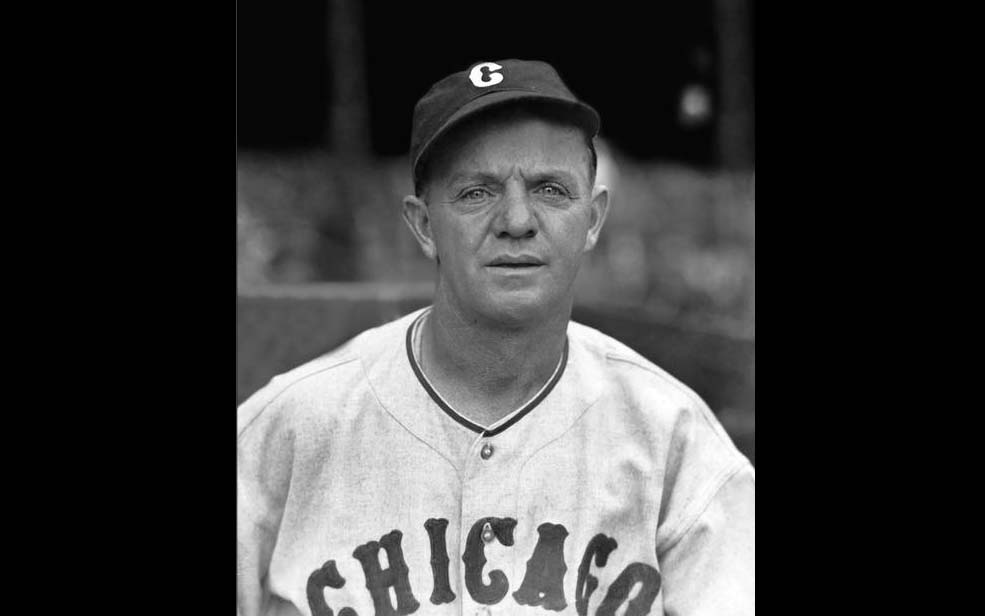

Local product fills gaping hole, brings Texas billionaire a championship

At the outset of 1934, Jim McLeod’s affiliation with professional baseball and that of the Texas League’s Galveston Buccaneers franchise owner Shearn Moody headed in opposite directions. Moody, 38-year-old heir to the famed Moody cotton, banking, and financial empire his father and grandfather had built on Galveston Island, had already stamped his Moody legacy on the insurance business. He was now making noise as a minor league baseball executive. McLeod, on the other hand, had played four professional baseball seasons, two-and-a-half in the big leagues. But he had failed to prove himself adequate at any level of the game.

Shearn Moody was a visionary. In the late 1920s, he saw Galveston’s future as a tourist destination. Shearn convinced the family to invest millions in the lodging industry both on and off the island. He also knew tourist destinations needed activities for visitors. While other island residents might invest in tourism eventually, Moody needed a popular attraction to help fill his hotels. A lifelong sportsman, Shearn Moody believed baseball to be just that attraction, and he staked both his reputation and money on it.

In 1931 Shearn Moody purchased a Texas League franchise, returning professional baseball to Galveston after a seven-year absence. Although a founding member of the Texas League and home to a franchise from 1888 to 1924, more pressing issues like rebuilding from the Great Storm of 1900, the 1915 Hurricane, and repeated outbreaks of yellow fever commanded local attention. Baseball was barely a diversion. But when Shearn Moody announced the Texas League had returned to Galveston, locals paid attention. After all, Moody didn’t settle for anything but the best, and it would be interesting to see how his endeavor played out. After two years as a league tail-ender, his Buccaneers fell just shy in 1933 when they lost in the Texas League championship series. For 1934, Moody and manager Billy Webb improved the lineup with a group of hitters to rival most big league clubs. When the season opened, both men had only one concern. The Buccaneer shortstops were weak.

Billy Webb’s strategic approach to his shortstop dilemma failed. With a platoon of three equally inept fielders, over the season’s first 62 games, Buccaneer shortstops committed 27 errors, on pace for 70 on the season. The trio’s batting did nothing to make up for their fielding miscues. At 32-30, Galveston was stuck in fifth place, needing at least fourth to make the playoffs. Webb and Moody searched baseball for a capable shortstop. The search ended in Portland, Oregon, with Jim McLeod of the Portland Beavers. By the end of June, McLeod plugged the shortstop hole, and the Buccaneers’ fortunes immediately changed.

As Galveston climbed in the standings, major league scouts made overtures for McLeod, but Shearn Moody, never one to shy from selling a player, held steadfast. Sportswriters soon bragged that McLeod had become the Texas League’s top shortstop. Galveston posted a 56-34 record the rest of the year, sitting atop the Texas League at season’s end. The Buccaneers knocked fourth place Dallas out of the playoffs in the first round, before claiming the Texas League Championship over San Antonio. When the dust settled, Shearn Moody had his trophy, and despite a lineup of bruising power hitters, the league’s most valuable player, and a pitching staff that produced six major leaguers, it was Jim McLeod who claimed unsung hero status.

McLeod’s 1934 success led Moody to keep him in Galveston through 1936. Before the 1936 season, however, Shearn Moody died of pneumonia at just 40 years old. The writing was on the wall. No other Moody family member had an interest in baseball, and the team was soon swept away to Shreveport.

Jim McLeod’s success in Galveston revived his baseball career. He never returned to the big leagues, but over the next seven years McLeod played in ten cities, mostly across the South. In early 1944, he enlisted in the Army and served a two-year stint. After WWII, McLeod returned to professional baseball as player-manager with Centerville of the Eastern Shore League. He went on to manage three more seasons in the New York Yankees organization, but 1946 represented Jim McLeod’s last as a ballplayer.

After following her husband across the country for over 15 years, Jim McLeod’s wife Julia, whom he married in 1933, was undoubtedly thrilled to return home to Little Rock. The couple had no children, but Jim stayed active in youth leagues as an umpire and basketball official, all while living within a few blocks of his childhood home next to what is now Central High School. He worked as a clerk and salesman for a majority of his non-baseball career, eventually retiring to his home on Montclair Road. He died of a pulmonary embolism on August 3, 1981.

If you visit UA-Little Rock today, you won’t find any sign of Jim McLeod. And chances are if you ask someone familiar with the school’s athletic history, McLeod won’t enter the conversation. But McLeod, despite never playing baseball at LRJC, is officially recorded as the first major league ballplayer having attended the school. Twenty years before organized baseball arrived on campus, in fact, the same athletic child who arrived in Little Rock from humble beginnings in south Arkansas brought a Texas billionaire the championship trophy he coveted. For that alone, Jim McLeod, the Little Rock schoolboy turned big leaguer, left his legacy in at least one of the six sports he’d lettered in back at West Side Junior High School.

Maumelle’s Kris Rutherford is the author of dozens of articles on Texas League baseball history as well as three books including, The Galveston Buccaneers: Shearn Moody and the 1934 Texas League Championship. He has been noted a leading expert on pre-WWII Texas League baseball.