State’s early banking attempts end badly

July 1-7, 2019

By Jay Edwards

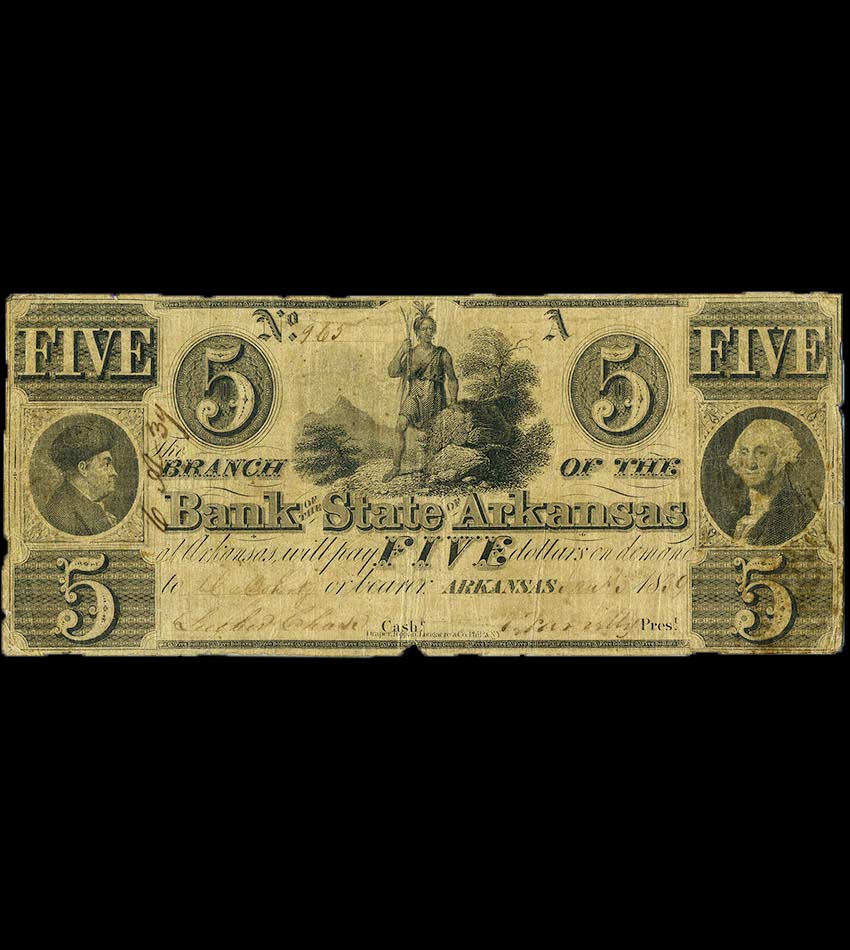

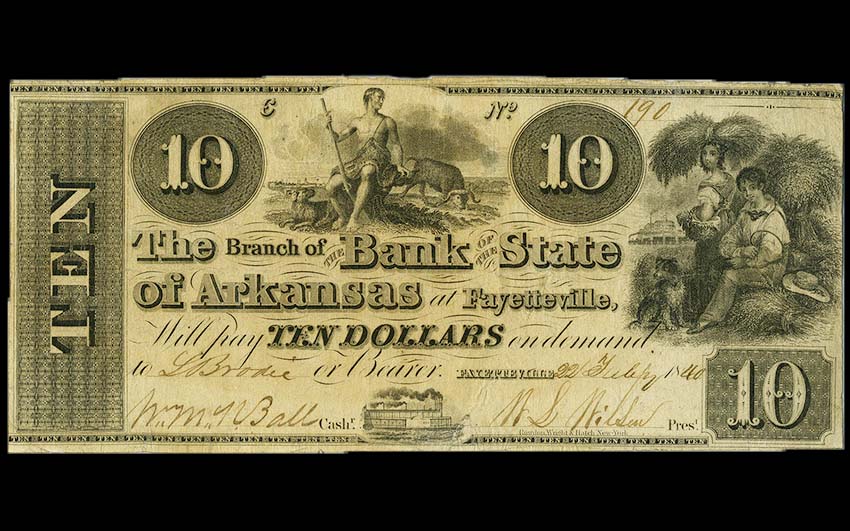

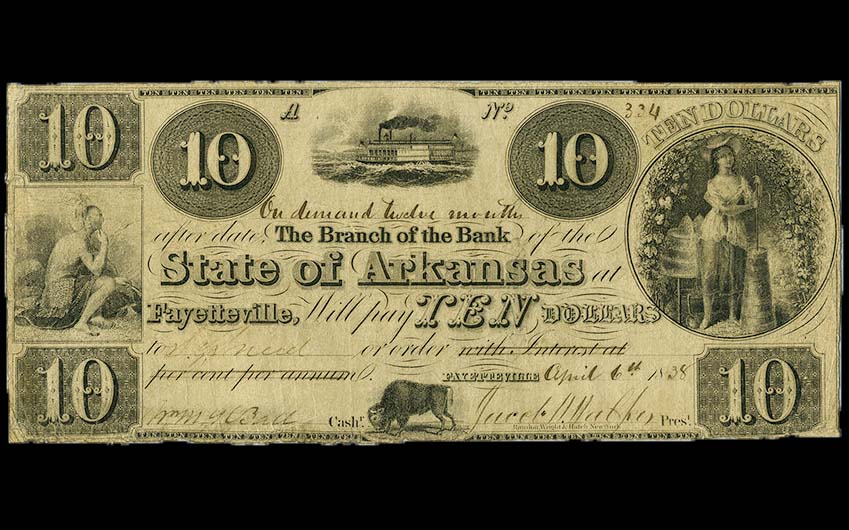

When the territory of Arkansas achieved statehood in 1836, one of the first things the governing powers decided was to try their hand at finance. From this vision two banks were created, the Arkansas State Bank and the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas. In 1837, the State Bank was chartered with one million dollars in capital. Five years later they were put into liquidation, with liabilities of around two million dollars.

The Real Estate Bank fared even worse and would produce tragic consequences.

The stated objective of the Real Estate Bank was to promote the interests of lowland planters in the Delta. Its capital stock was valued at two million dollars for which the state issued two thousand bonds valued at a thousand dollars each. There were 325 people who subscribed to the initial offering, and they typically bought stock by borrowing against their land, which was valued at inflated prices to allow them to buy more stock. They were given ten years to pay back the loan.

The bank had some difficulty moving the bonds and ended up selling 500 ($500,000) to the secretary of the U.S. Treasury for the Smithsonian Institution, and 1000 more to the North American Trust and Banking Company of New York. Later, when the Real Estate Bank was struggling to pay the interest on the bonds, it borrowed money from North American Trust, putting up the remaining 500 bonds as collateral, expecting to get $250,000. But they only received $121,336 from North American Trust, who ended up selling the 500 bonds to a banker in London named James Holford, for $325,000. Not long after, North American Trust also failed, but not before making over $200,000 in its transactions with the Arkansas bonds.

After the failure of the Real Estate Bank, attempts to convert the bank’s assets into money began, which lasted for decades. The trustees led the efforts for 13 years, finally relinquishing their power to the courts. In 1858 the bank still had debts of over 2.2 million dollars, with assets of around $900,000. The state was on the hook now for $2.5 million, adding in the failure of the Arkansas State Bank.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, all action on bank matters regarding the state were suspended. It was not until 1874 that a decree was made that gave landowners a 15 year installment plan to pay the mortgages on their collateralized lands, before foreclosure proceedings. Under the new structure, all of the bonds, even the disputed Holford’s, could be exchanged for new bonds with a 25-year term paying six percent interest.

As for the Holford bonds, the state legislature addressed them again in 1879, when Colonel William M. Fishback proposed an amendment that they not be paid, as they had been pledged contrary to the law. Many opposed the amendment, including the Arkansas Gazette, and it was defeated more than once. Then in 1884 its proponents rallied again, and it became, and remains, Amendment Number 1 of the Arkansas Constitution.

Deadly repercussion

When the 1837 legislative session rolled around, grumblings of scheming favoritism and gross mismanagement of funds were heard throughout the chamber of the State House. One of the most vocal of critics was the representative from Randolph County, Joseph J. Anthony, a native of Virginia who moved to middle Tennessee when he was in his early twenties, along with his Baptist minister father and the rest of the family. Anthony joined the army at the outbreak of the War of 1812 and became a first lieutenant. He resigned his commission over allegations of dereliction of duty and cowardice, to avoid a court-martial. Anthony forever denied the charges and later redeemed himself, reenlisting and serving with distinction under Andrew Jackson, against the Creek Indians in Alabama.

At the end of the war he returned to Tennessee, later moving to Missouri before finally settling in the Arkansas Territory in 1835.

When the Real Estate Bank was chartered, officers needed to be put in place and the president’s duties were given to John Wilson of Clark County, who was speaker of the house in the young legislature. Wilson seemed as surprised as anyone that the bank had chosen him, but he agreed to take the job on a temporary basis. In the “Historical Review of Arkansas,” Fay Hempstead wrote, “Judge Daniel T. Witter, who knew (Wilson) well, said of him that he was a man of ‘strong personality and companionable, except when his temper was aroused.’”

On Dec. 4, 1837, Wilson arrived late to the house of representative’s hall at the state house. In truth, his tardiness was caused by conversation regarding some less than flattering remarks about his new position at the Real Estate Bank.

Wilson found his seat and listened to the reading of the first order of business, which was a bill on the floor about the offering of bounties for the killing of timber wolves.

Anthony said that instead of being issued by a magistrate, the wolf bounty’s should be handled by the president of the Real Estate Bank. Wilson looked up and asked if Anthony had meant the suggestion as an insult. Anthony replied, “I believe there should be more dignity attached to the office of one who receives oaths in the state of Arkansas. Strike out magistrate and write in, say, President of the Real Estate Bank.”

There was nervous laughter at this, which ceased when Wilson jumped down from the podium and pulled out his nine-inch Bowie knife. But Anthony was prepared, drawing a 12-inch blade of his own, and the dueling lawmakers faced each other down.

Grandison D. Royston, the representative from Hempstead County and self-appointed peacemaker, grabbed a chair and placed it between the two jousters. But both men began slashing at the air, trying to wound the other. Anthony drew first blood, hitting Wilson’s wrist hard and deep, almost severing his left hand and causing him to back up. Then, as later reported in “The Whig Review,” Anthony threw his knife at Wilson, striking him not with the point, but on the flat side, and the knife fell to the floor. Wilson struck back fast. Using the chair for leverage under his left elbow, he thrust his blade upward with his good hand, into Anthony’s body, who slumped and was dead in seconds.

Wilson was taken into custody and detained at the Jesse Hinderliter house. He was indicted for murder, received a change of venue to Saline County for his trial, and was acquitted on grounds of self-defense.

Anthony was buried in Little Rock’s old “public grave-yard,” located where the Little Rock Federal Building now stands on Capitol Avenue. There is good reason to believe that his remains still reside somewhere at the site since his name is not among those listed as being removed to Mount Holly Cemetery in 1860.

Sources: Encyclopedia of Arkansas; Historical Review of Arkansas: Its Commerce, Industry and Modern Affairs by Fay Hempstead, Vol. 1, 1911; Arkansas Road Stories: The Old State House

PHOTO CAPTION:

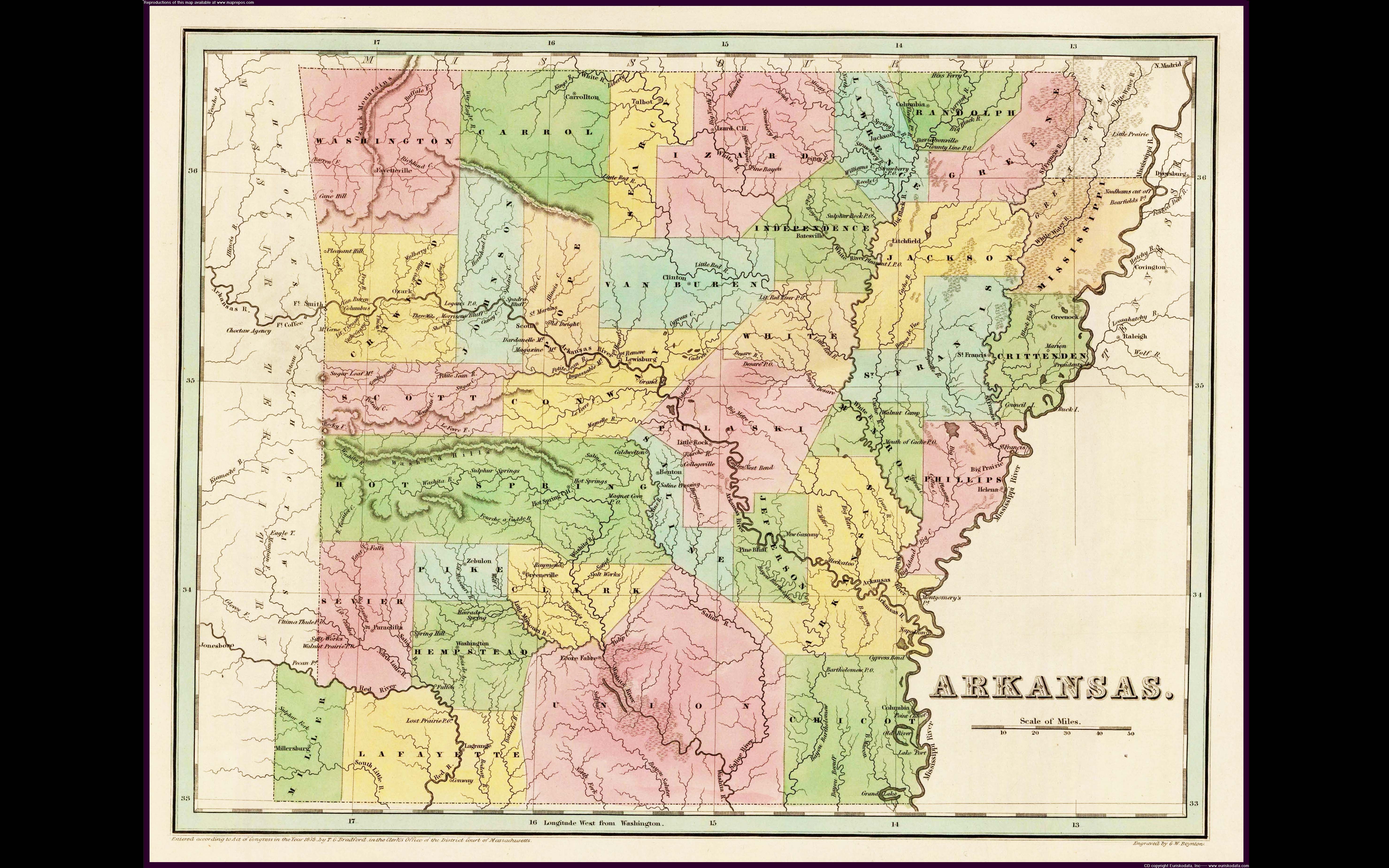

During early statehood, Arkansas struggled and eventually failed to create a solid banking system. Discover what became of the Arkansas State Bank and the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas. (Historic map courtesy of Pine Bluff Jefferson County Library System)